News

Catch up on what’s happening in the world of global citizenship education.

1,657 results found

Korea Youth Sustainable Development Council, SDGs Youth Builder Academy 2nd lecture 'Global Citizenship Education' held... Successful completion 2022-11-02 [Korea Youth Council News / Intern Reporter Kwon Hyo-min] On October 28th, the Korea Youth Sustainable Development Council (hereafter Cheong Ji-hyeop) conducted 'Global Citizenship Education' as the second lecture of the SDGs Youth Builder Academy. Following the first lecture with the theme of 'Peace and Human Rights', many young people interested in sustainable peace participated again this time. First, the academy opened with global citizenship education. The lecture was conducted by invited lecturer Lee Ji-yeon of the Hi Global Citizenship Education Instructor Council. This lecturer, who said that he has more foreign friends than Korean friends, shared with the young people what he had experienced while traveling around the world. It showed that even people of different cultures can form deep relationships with each other, and emphasized the responsibility of global citizens to respect diversity and coexist. In addition, this lecturer explained that most of the refugees who cause terrorism are those who have experienced hatred and discrimination, and argued that hating and excluding refugees has rather negative consequences. Therefore, it conveyed the message that refugees entering Korea should be treated with hospitality rather than hate. After the global citizenship education, in October, we had time to share best practices for the 'Peace and Human Rights' mission. Recalling the 'Refugee Refugee NGO Afghan Consultation' held on October 1 and the 'IOM Seminar on the Rights of the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities' held on October 6, youth builders were able to reflect on their activities in the beginning of October. In addition, remembering the 'Refugee Education for Refugees' held on October 18 and the latest video of the Ukraine-Russian War watched on the 19th of the same month, we also shared the activities of the second half of October, and what activities young people can do for sustainable peace. I had time to look back on what I did. In addition, each individual shared their personal activities and donations to discuss small changes in their practices and ideas they would like to propose in the future. It was a place for dialogue to remind us that human beings can help each other, solidarize, and create a peaceful world, free from hate and war. As the last ceremony, we had time to guide the SDG Youth Builder mission in November. The theme of the November SDGs implementation mission is “Living as a global citizen”. After listening to this lecture, youth builders will find, plan, and execute activities that they can practice, and conduct a performance report in November. The goal is to enable people to move forward as global citizens through practices that respect diversity regardless of race, religion, or nationality. The second lecture of the SDGs Youth Builder Academy was concluded with the announcement that the third lecture of the next academy will be conducted under the theme of 'disability and human rights'. CEO Jeongpil Kim, who also successfully concluded this event, said about the significance of this education, “Peace and partnership, one of the 17 goals and prerequisites of the SDGs, seems to ‘start with human rights and end with human rights’.” Education is the foundation for thinking about the rights of all people in the global village beyond the Korean Peninsula by examining how we living in Korea are connected to each other and how citizens living in different continents and cultures are connected to each other and how each other's actions affect each other. It was very meaningful to be prepared.” URL: https://www.mediayouth.kr/news/668052

Korea Youth Sustainable Development Council, SDGs Youth Builder Academy 2nd lecture 'Global Citizenship Education' held... Successful completion 2022-11-02 [Korea Youth Council News / Intern Reporter Kwon Hyo-min] On October 28th, the Korea Youth Sustainable Development Council (hereafter Cheong Ji-hyeop) conducted 'Global Citizenship Education' as the second lecture of the SDGs Youth Builder Academy. Following the first lecture with the theme of 'Peace and Human Rights', many young people interested in sustainable peace participated again this time. First, the academy opened with global citizenship education. The lecture was conducted by invited lecturer Lee Ji-yeon of the Hi Global Citizenship Education Instructor Council. This lecturer, who said that he has more foreign friends than Korean friends, shared with the young people what he had experienced while traveling around the world. It showed that even people of different cultures can form deep relationships with each other, and emphasized the responsibility of global citizens to respect diversity and coexist. In addition, this lecturer explained that most of the refugees who cause terrorism are those who have experienced hatred and discrimination, and argued that hating and excluding refugees has rather negative consequences. Therefore, it conveyed the message that refugees entering Korea should be treated with hospitality rather than hate. After the global citizenship education, in October, we had time to share best practices for the 'Peace and Human Rights' mission. Recalling the 'Refugee Refugee NGO Afghan Consultation' held on October 1 and the 'IOM Seminar on the Rights of the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities' held on October 6, youth builders were able to reflect on their activities in the beginning of October. In addition, remembering the 'Refugee Education for Refugees' held on October 18 and the latest video of the Ukraine-Russian War watched on the 19th of the same month, we also shared the activities of the second half of October, and what activities young people can do for sustainable peace. I had time to look back on what I did. In addition, each individual shared their personal activities and donations to discuss small changes in their practices and ideas they would like to propose in the future. It was a place for dialogue to remind us that human beings can help each other, solidarize, and create a peaceful world, free from hate and war. As the last ceremony, we had time to guide the SDG Youth Builder mission in November. The theme of the November SDGs implementation mission is “Living as a global citizen”. After listening to this lecture, youth builders will find, plan, and execute activities that they can practice, and conduct a performance report in November. The goal is to enable people to move forward as global citizens through practices that respect diversity regardless of race, religion, or nationality. The second lecture of the SDGs Youth Builder Academy was concluded with the announcement that the third lecture of the next academy will be conducted under the theme of 'disability and human rights'. CEO Jeongpil Kim, who also successfully concluded this event, said about the significance of this education, “Peace and partnership, one of the 17 goals and prerequisites of the SDGs, seems to ‘start with human rights and end with human rights’.” Education is the foundation for thinking about the rights of all people in the global village beyond the Korean Peninsula by examining how we living in Korea are connected to each other and how citizens living in different continents and cultures are connected to each other and how each other's actions affect each other. It was very meaningful to be prepared.” URL: https://www.mediayouth.kr/news/668052  Wenhui Award 2022 Call for Applications and Nominations: “Educational Innovations for Learning Recovery” 2022-10-31 The Transforming Education Summit convened by the United Nations in September 2022 mobilized over 130 countries to explore all options and innovations in response to the major challenges in education, including the catastrophic learning losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises. The coronavirus has disrupted education systems all over the world, with more than 1.6 billion learners affected by school closures. The Asia-Pacific is one of the most hit regions. Approximately 1.2 billion students across the region have in total lost about 1.1 trillion hours of in-person learning as a result of school closures during COVID-19 outbreaks. The pandemic has exacerbated inequalities in education, with the disadvantaged groups suffering more, including girls, children with disabilities, and students from low-income families, ethnic minorities and remote rural areas. COVID-19 has also deepened the pre-existing learning crisis. The learning poverty rate – the share of children who cannot read a simple text with comprehension by age 10 – has significantly risen in low- and middle-income countries, with South Asia seeing one of the highest increases. Such severe learning losses have devastating socio-economic implications. The productivity and lifetime earnings of affected students are projected to decrease, and the unemployment rate in many societies is estimated to increase, which will aggravate poverty and backslash the long-term economic growth. Besides, disproportional learning loss has further widened income inequalities between and within countries. Apart from COVID-19, other types of crises and emergencies – violence, armed conflict, diseases, refugee and internal displacement, natural hazards including climate-induced disasters, food shortage and poverty – also contribute to learning losses. Even prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the global number of crisis-impacted school-aged children requiring educational support had grown significantly. Learning recovery from different crises has been placed on the high agenda of the international community. It means not only bringing all learners back to school and achieving effective remedial learning, but also improving and sustaining the wellbeing and development of students and teachers, filling divides, and equipping youth with the competences and skills for life, work, and sustainable development. A powerful engine for learning recovery is education innovation, which is critical for inclusive, equitable, and quality education as well. In its broadened sense, educational innovation involves all dimensions of the education ecosystem, including but not limited to 1) innovations for inclusive, equitable, safe, and healthy schools; 2) teaching innovations to cultivate competences and skills for life, work, and sustainable development; 3) innovations in digital learning; 4) innovations for the development of the teaching profession; 5) innovations in education financing; and 6) innovations in education partnerships. Globally and in the Asia-Pacific region in particular, various innovative education policies and practices have emerged and accelerated learning recovery. However, despite the existing efforts and achievements, many societies are still suffering lingering learning losses. Concerted endeavours are needed to invigorate education innovations for effective learning recovery across the world. About Wenhui AwardAgainst the above background, this year’s Wenhui Award is themed “Educational Innovations for Learning Recovery”, with the objective to identify, acknowledge and encourage innovative policies and practices in various dimensions of the education system in the Asia-Pacific region. The Award shall be conferred on two individuals or institutions in the Asia-Pacific region for their outstanding efforts and achievements in educational innovation about this year’s theme. The two winners will each receive a Certificate of Excellence and a prize of USD20,000. Apart from the winners, Honourable Mentions will be granted to individuals or institutions that have demonstrated commendable innovative educational practices. The Wenhui (文晖) Award was jointly created by the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Programme of Educational Innovation for Development (APEID) and the National Commission of the People’s Republic of China for UNESCO in 2010, to recognize and reward individuals or institutions that have made outstanding contributions to educational innovation in the Asia-Pacific region. Since the inception of the Wenhui Award, there have been 22 Winners and 34 Honourable Mentions from 19 different countries. Eligibility and Assessment CriteriaEligibility of Applicants:• Be individuals or institutions from UNESCO Member States in the Asia-Pacific region ;• Have initiated, developed and implemented innovative practices that are in line with the latest developments in education in the 21st century and that help to improve access, equity and quality of education in the Asia-Pacific region;• Have proved that their innovations have exerted positive impacts on education opportunities and quality in the Asia-Pacific region;• Be persistently dedicated to popularization of education, enhancement of education quality, and promotion of lifelong learning. Assessment Criteria for the Innovations:All the educational innovations submitted for the Wenhui Award will be assessed equally against the following criteria:1. Relevance (to the latest developments in education in the 21st century; to Sustainable Development Goal 4 aiming to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all; to the Asia-Pacific region; AND to the specific theme of the Award of the year);2. Timeliness (started within the recent 3 years, with the key part completed by the time of application);3. Effectiveness (in tackling specific challenges/issues in education); 4. Scale of benefits and impacts (evidenced by specific indicators, such as number of beneficiary countries in the Asia-Pacific region, number of beneficiary schools, number of beneficiary students, teachers, school leaders, and community members);5. Engagement of stakeholders and partners from different sectors (public and non-public), if applicable;6. Originality (how creative and unique the innovation is);7. Sustainability (of the good practices, benefits and positive impacts of the innovation), scalability (the capacity to expand in coverage and grow in impact without much extra resources), and replicability (to other educational institutions, stakeholder groups, and even possibly other countries and regions). Application Procedure and Required MaterialsApplications for Wenhui Award can be submitted in the following two alternative channels:Channel A. Direct ApplicationApplicants directly submit the required materials (listed below) to the Wenhui Award Secretariat at the email address Wenhui.Award(at)unesco.org by 27 January 2023, 23:59 Bangkok time (UTC+7). Channel B. Nominator-Initiated ApplicationThe National Commissions for UNESCO or UNESCO Field Offices in the Asia-Pacific Member States identify potentially qualified applicants and innovations, invite them to submit all the required materials to the nominator by a specific date, and then nominate them to the Wenhui Award Secretariat. Nominators shall send all the required materials (listed below) and the nomination letter (signed and stamped) by email to the Wenhui Award Secretariat by 24 February 2023, 23:59 Bangkok time (UTC+7). Information on National Commissions for UNESCO: https://en.unesco.org/countries/national-commissions.Information on UNESCO Field Offices: https://en.unesco.org/countries/field-offices.*Only UNESCO National Commissions and Field Offices can be nominators for the Wenhui Award, and applicants from Channel A need to indicate their preferred nominator in the application form.*Such nominations should be initiated by UNESCO National Commissions or Field Offices in the Asia-Pacific region. Applicants do not need to contact the potential nominators. Required Materials:1. A fully completed application form (https://bit.ly/Wenhui22AFA) or nomination form (https://bit.ly/Wenhui22NFB); 2. Detailed introduction of the innovation, using the given template (https://bit.ly/Wenhui22TDS);3. Supporting materials, including at least one of the following:a) brochure of the innovation (no more than 12 pages, in PDF format);b) link to photos (no more than 5, in JPG or PDF format) or a video (within 5 minutes) about the innovation;c) link to the website of the innovation;d) link(s) to the social media platform(s) of the innovation;e) media coverage on the innovation (either the web link or PDF version).*The above list is for both direct applications and nominator-initiated applications; for nominator-initiated applications, the nominators need to collect all the required materials from the nominees and then submit them to the Wenhui Award Secretariat.*All the links should be put on the application/nomination form, while the PDF documents need to be sent by email to the Wenhui Award Secretariat together with all the other application/nomination documents. Selection ProcessStep 1: Pre-Screening The Wenhui Award Secretariat will pre-screen all applications received by the deadline based on the eligibility and assessment criteria. Step 2: Selection by Nominators*This step is only for applications directly submitted to the Wenhui Award Secretariat (Channel A), and applicants do not need to initiate contact with any potential nominator.The Wenhui Award Secretariat will send the applications that have passed prescreening to the nominators chosen by the applicants themselves, either UNESCO National Commissions or Field Offices. The nominators will review and decide whether to nominate the applicants for further selection. The nominators shall directly send the nomination letters by email to the Wenhui Award Secretariat. The letter should comment on the applicant’s eligibility for the Award and provide additional information if deemed necessary by the nominator. Step 3: Shortlisting Upon receiving the nomination letters for direct applications (Channel A), the Wenhui Award Secretariat will further review and shortlist based on the eligibility and assessment criteria. For those nominations initiated directly by UNESCO National Commissions and Field Offices (Channel B), the Secretariat will also conduct prescreening and shortlisting based on the same criteria.Step 4: Final AssessmentThe final assessment of shortlisted applications is conducted by a Jury consisting of multiple members who are from different countries and organizations in the Asia-Pacific region and have extensive expertise and experience in education.Step 5: Result AnnouncementThe winners of the Award and the recipients of the Honourable Mentions will be notified by email shortly after the Jury has made its final decisions, and upon written confirmation of acceptance, the results will be officially announced online in due course. The winners will be invited to the Award Ceremony to be held virtually or in person in China. Inquiries & ContactFor inquiries about Wenhui Award application, nomination, and selection process, please check the above information and Frequently Asked Questions at https://bit.ly/Wenhui22FAQ. If you have any further inquiries, please contact the Wenhui Award Secretariat at Wenhui.Award(at)unesco.org. URL: https://bangkok.unesco.org/index.php/content/wenhui-award-2022-call-applications-nominations-educational-innovations-learning-recovery-unesco

Wenhui Award 2022 Call for Applications and Nominations: “Educational Innovations for Learning Recovery” 2022-10-31 The Transforming Education Summit convened by the United Nations in September 2022 mobilized over 130 countries to explore all options and innovations in response to the major challenges in education, including the catastrophic learning losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises. The coronavirus has disrupted education systems all over the world, with more than 1.6 billion learners affected by school closures. The Asia-Pacific is one of the most hit regions. Approximately 1.2 billion students across the region have in total lost about 1.1 trillion hours of in-person learning as a result of school closures during COVID-19 outbreaks. The pandemic has exacerbated inequalities in education, with the disadvantaged groups suffering more, including girls, children with disabilities, and students from low-income families, ethnic minorities and remote rural areas. COVID-19 has also deepened the pre-existing learning crisis. The learning poverty rate – the share of children who cannot read a simple text with comprehension by age 10 – has significantly risen in low- and middle-income countries, with South Asia seeing one of the highest increases. Such severe learning losses have devastating socio-economic implications. The productivity and lifetime earnings of affected students are projected to decrease, and the unemployment rate in many societies is estimated to increase, which will aggravate poverty and backslash the long-term economic growth. Besides, disproportional learning loss has further widened income inequalities between and within countries. Apart from COVID-19, other types of crises and emergencies – violence, armed conflict, diseases, refugee and internal displacement, natural hazards including climate-induced disasters, food shortage and poverty – also contribute to learning losses. Even prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the global number of crisis-impacted school-aged children requiring educational support had grown significantly. Learning recovery from different crises has been placed on the high agenda of the international community. It means not only bringing all learners back to school and achieving effective remedial learning, but also improving and sustaining the wellbeing and development of students and teachers, filling divides, and equipping youth with the competences and skills for life, work, and sustainable development. A powerful engine for learning recovery is education innovation, which is critical for inclusive, equitable, and quality education as well. In its broadened sense, educational innovation involves all dimensions of the education ecosystem, including but not limited to 1) innovations for inclusive, equitable, safe, and healthy schools; 2) teaching innovations to cultivate competences and skills for life, work, and sustainable development; 3) innovations in digital learning; 4) innovations for the development of the teaching profession; 5) innovations in education financing; and 6) innovations in education partnerships. Globally and in the Asia-Pacific region in particular, various innovative education policies and practices have emerged and accelerated learning recovery. However, despite the existing efforts and achievements, many societies are still suffering lingering learning losses. Concerted endeavours are needed to invigorate education innovations for effective learning recovery across the world. About Wenhui AwardAgainst the above background, this year’s Wenhui Award is themed “Educational Innovations for Learning Recovery”, with the objective to identify, acknowledge and encourage innovative policies and practices in various dimensions of the education system in the Asia-Pacific region. The Award shall be conferred on two individuals or institutions in the Asia-Pacific region for their outstanding efforts and achievements in educational innovation about this year’s theme. The two winners will each receive a Certificate of Excellence and a prize of USD20,000. Apart from the winners, Honourable Mentions will be granted to individuals or institutions that have demonstrated commendable innovative educational practices. The Wenhui (文晖) Award was jointly created by the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Programme of Educational Innovation for Development (APEID) and the National Commission of the People’s Republic of China for UNESCO in 2010, to recognize and reward individuals or institutions that have made outstanding contributions to educational innovation in the Asia-Pacific region. Since the inception of the Wenhui Award, there have been 22 Winners and 34 Honourable Mentions from 19 different countries. Eligibility and Assessment CriteriaEligibility of Applicants:• Be individuals or institutions from UNESCO Member States in the Asia-Pacific region ;• Have initiated, developed and implemented innovative practices that are in line with the latest developments in education in the 21st century and that help to improve access, equity and quality of education in the Asia-Pacific region;• Have proved that their innovations have exerted positive impacts on education opportunities and quality in the Asia-Pacific region;• Be persistently dedicated to popularization of education, enhancement of education quality, and promotion of lifelong learning. Assessment Criteria for the Innovations:All the educational innovations submitted for the Wenhui Award will be assessed equally against the following criteria:1. Relevance (to the latest developments in education in the 21st century; to Sustainable Development Goal 4 aiming to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all; to the Asia-Pacific region; AND to the specific theme of the Award of the year);2. Timeliness (started within the recent 3 years, with the key part completed by the time of application);3. Effectiveness (in tackling specific challenges/issues in education); 4. Scale of benefits and impacts (evidenced by specific indicators, such as number of beneficiary countries in the Asia-Pacific region, number of beneficiary schools, number of beneficiary students, teachers, school leaders, and community members);5. Engagement of stakeholders and partners from different sectors (public and non-public), if applicable;6. Originality (how creative and unique the innovation is);7. Sustainability (of the good practices, benefits and positive impacts of the innovation), scalability (the capacity to expand in coverage and grow in impact without much extra resources), and replicability (to other educational institutions, stakeholder groups, and even possibly other countries and regions). Application Procedure and Required MaterialsApplications for Wenhui Award can be submitted in the following two alternative channels:Channel A. Direct ApplicationApplicants directly submit the required materials (listed below) to the Wenhui Award Secretariat at the email address Wenhui.Award(at)unesco.org by 27 January 2023, 23:59 Bangkok time (UTC+7). Channel B. Nominator-Initiated ApplicationThe National Commissions for UNESCO or UNESCO Field Offices in the Asia-Pacific Member States identify potentially qualified applicants and innovations, invite them to submit all the required materials to the nominator by a specific date, and then nominate them to the Wenhui Award Secretariat. Nominators shall send all the required materials (listed below) and the nomination letter (signed and stamped) by email to the Wenhui Award Secretariat by 24 February 2023, 23:59 Bangkok time (UTC+7). Information on National Commissions for UNESCO: https://en.unesco.org/countries/national-commissions.Information on UNESCO Field Offices: https://en.unesco.org/countries/field-offices.*Only UNESCO National Commissions and Field Offices can be nominators for the Wenhui Award, and applicants from Channel A need to indicate their preferred nominator in the application form.*Such nominations should be initiated by UNESCO National Commissions or Field Offices in the Asia-Pacific region. Applicants do not need to contact the potential nominators. Required Materials:1. A fully completed application form (https://bit.ly/Wenhui22AFA) or nomination form (https://bit.ly/Wenhui22NFB); 2. Detailed introduction of the innovation, using the given template (https://bit.ly/Wenhui22TDS);3. Supporting materials, including at least one of the following:a) brochure of the innovation (no more than 12 pages, in PDF format);b) link to photos (no more than 5, in JPG or PDF format) or a video (within 5 minutes) about the innovation;c) link to the website of the innovation;d) link(s) to the social media platform(s) of the innovation;e) media coverage on the innovation (either the web link or PDF version).*The above list is for both direct applications and nominator-initiated applications; for nominator-initiated applications, the nominators need to collect all the required materials from the nominees and then submit them to the Wenhui Award Secretariat.*All the links should be put on the application/nomination form, while the PDF documents need to be sent by email to the Wenhui Award Secretariat together with all the other application/nomination documents. Selection ProcessStep 1: Pre-Screening The Wenhui Award Secretariat will pre-screen all applications received by the deadline based on the eligibility and assessment criteria. Step 2: Selection by Nominators*This step is only for applications directly submitted to the Wenhui Award Secretariat (Channel A), and applicants do not need to initiate contact with any potential nominator.The Wenhui Award Secretariat will send the applications that have passed prescreening to the nominators chosen by the applicants themselves, either UNESCO National Commissions or Field Offices. The nominators will review and decide whether to nominate the applicants for further selection. The nominators shall directly send the nomination letters by email to the Wenhui Award Secretariat. The letter should comment on the applicant’s eligibility for the Award and provide additional information if deemed necessary by the nominator. Step 3: Shortlisting Upon receiving the nomination letters for direct applications (Channel A), the Wenhui Award Secretariat will further review and shortlist based on the eligibility and assessment criteria. For those nominations initiated directly by UNESCO National Commissions and Field Offices (Channel B), the Secretariat will also conduct prescreening and shortlisting based on the same criteria.Step 4: Final AssessmentThe final assessment of shortlisted applications is conducted by a Jury consisting of multiple members who are from different countries and organizations in the Asia-Pacific region and have extensive expertise and experience in education.Step 5: Result AnnouncementThe winners of the Award and the recipients of the Honourable Mentions will be notified by email shortly after the Jury has made its final decisions, and upon written confirmation of acceptance, the results will be officially announced online in due course. The winners will be invited to the Award Ceremony to be held virtually or in person in China. Inquiries & ContactFor inquiries about Wenhui Award application, nomination, and selection process, please check the above information and Frequently Asked Questions at https://bit.ly/Wenhui22FAQ. If you have any further inquiries, please contact the Wenhui Award Secretariat at Wenhui.Award(at)unesco.org. URL: https://bangkok.unesco.org/index.php/content/wenhui-award-2022-call-applications-nominations-educational-innovations-learning-recovery-unesco  Asia-Pacific Teachers Embrace UNESCO Challenge to Bring Local Living Heritage into Their Classrooms 2022-10-31 28 October 2022 – Since 2019, UNESCO, with support from International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (UNESCO-ICHCAP), Asia-Pacific Centre of Education for International Understanding (APCEIU), and Chengdu Culture and Tourism Development Group L.L.C., has run a project, Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage (ICH) in formal education in Asia and the Pacific. The project aims to develop and pilot innovative activities with teachers, students and heritage bearers in schools, encourage experience-sharing among teachers in different countries, and engage local education sectors in achieving quality education for all through the safeguarding of the living heritage of local communities. Recently commenting on the project’s success, to date, Mr Seng Song, a coordinator of culture and arts education of Cambodian Living Arts, a non-governmental educational organization in Phnom Penh, noted, ‘The school directors were really excited and showed us very positive responses, especially given the fact that since they started using ICH, or living heritage, in their local subjects, they observed changes in the way students learn. (The students] have become more active and creative.’ Mr Song added, ‘ICH Education, as [teachers] call it, has become a method to unleash the talents of their students, such as their teamwork ability, critical thinking and idea presentation. It creates an environment that makes students happy and curious; hence, the become more interactive with teachers.’ While many observers might think that living heritage can only possibly be integrated in arts and religion classes, many teachers have revealed that this approach is applicable to other subjects, from social studies to geography, and even to mathematics and the sciences. ‘The goals of my lessons in social studies are [for students] to achieve an awareness of the importance of human rights, and to internalize a positive attitude toward human rights protection. I want the students to realize that the process by which injustice is felt by ordinary people could come to a critical point to form public opinions across the society, [which signals] the progress of human rights’, said Mr Hojeong Kim, a teacher at Shingal Elemenary School, in Yongin, the Republic of Korea. ‘My favourite part is that I can provide educational experiences while keeping the students engaged. We did fun physical and expressive activities, learning about the philosophical ideas instilled in the choreography of the namsadang nori performing art, and applying these ideas to the student’s lives. We look at elements of social critique in Korean pop songs, then find such critique in the performance script of the troupes.’ Mr Kim also commented that intangible cultural heritage is ‘an accumulation of experiences, lifestyles and cultures of people in certain areas. It is a great example of human adaptation to the environment, and their efforts to sustain communities and solve problems; thus, it is closely related to education. We expand the student’s temporal horizons by getting them to learn about past culture through the intangible heritage of the present day and predicting cultural changes in the future.’ In 2021, the project produced several guiding and outreach materials with lesson plans on how to integrate intangible heritage in schools, so that more schools across the region might enjoy such positive learning experience. These materials were transformed into a self-learning course for teachers and educators on GCED Online Campus, and a resource kit available in several languages. The project also produced a cohort of interdisciplinary educators in six pilot countries, namely Cambodia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyztan, Nepal, Republic of Korea and Thailand. ‘I have found that integrating living heritage into educational curricula is very useful for learners’, Mr Manit Ta-ai, Director of Ton Kaew Phadung Pitayalai School, in Chiang Mai, Thailand, commented on the subject of methodology. ‘The important thing is to provide our students with opportunities to think and analyze, so that it will reflect on their abilities to build their future upon various cultural assets they were born with, such as incorporating traditional knowledge to creative production of their own. Proving platforms and ways for students to learn directly from local masters can maximize the benefits of local cultural resources – both tangible and intangible heritage – to achieve inclusive and affordable education.’ This year, UNESCO is running quarterly challenges to teachers across Asia-Pacific, through UNESCO Associated Schools Network (ASPnet) and SEAMEO Schools’ Network. The three-step challenge calls for teachers to complete the GCED Online Campus course ‘Bringing Living Heritage to the Classroom in Asia-Pacific’, then to sign up for a regional webinar to wrap up their knowledge with the course developers, and finally to share with UNESCO their newly-developed lesson plans that integrate their local living heritage with the teaching of existing subjects. The first quarterly webinar, which took place on 30 September 2022, was attended by over 150 teachers across the region, with numerous lesson plans submitted by participants after its conclusion. The second quarterly webinar will take place on 1 December 2022, via Zoom conferencing. Teachers and educators interested in joining this growing community and taking up UNESCO’s challenge, thereby becoming eligible to earn up to three professional development certificates, can find further information at https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/teachers-living-heritage-online-course-engaging-class-culture The last step of the challenge – sharing your lesson plan with UNESCO – will end on 31 December 2022, after which UNESCO will respond directly to all submitters with comments for improving and actualizing their aspiring lesson plans.URL: https://bangkok.unesco.org/index.php/content/asia-pacific-teachers-embrace-unesco-challenge-bring-local-living-heritage-classrooms

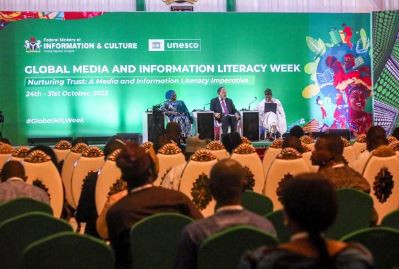

Asia-Pacific Teachers Embrace UNESCO Challenge to Bring Local Living Heritage into Their Classrooms 2022-10-31 28 October 2022 – Since 2019, UNESCO, with support from International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (UNESCO-ICHCAP), Asia-Pacific Centre of Education for International Understanding (APCEIU), and Chengdu Culture and Tourism Development Group L.L.C., has run a project, Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage (ICH) in formal education in Asia and the Pacific. The project aims to develop and pilot innovative activities with teachers, students and heritage bearers in schools, encourage experience-sharing among teachers in different countries, and engage local education sectors in achieving quality education for all through the safeguarding of the living heritage of local communities. Recently commenting on the project’s success, to date, Mr Seng Song, a coordinator of culture and arts education of Cambodian Living Arts, a non-governmental educational organization in Phnom Penh, noted, ‘The school directors were really excited and showed us very positive responses, especially given the fact that since they started using ICH, or living heritage, in their local subjects, they observed changes in the way students learn. (The students] have become more active and creative.’ Mr Song added, ‘ICH Education, as [teachers] call it, has become a method to unleash the talents of their students, such as their teamwork ability, critical thinking and idea presentation. It creates an environment that makes students happy and curious; hence, the become more interactive with teachers.’ While many observers might think that living heritage can only possibly be integrated in arts and religion classes, many teachers have revealed that this approach is applicable to other subjects, from social studies to geography, and even to mathematics and the sciences. ‘The goals of my lessons in social studies are [for students] to achieve an awareness of the importance of human rights, and to internalize a positive attitude toward human rights protection. I want the students to realize that the process by which injustice is felt by ordinary people could come to a critical point to form public opinions across the society, [which signals] the progress of human rights’, said Mr Hojeong Kim, a teacher at Shingal Elemenary School, in Yongin, the Republic of Korea. ‘My favourite part is that I can provide educational experiences while keeping the students engaged. We did fun physical and expressive activities, learning about the philosophical ideas instilled in the choreography of the namsadang nori performing art, and applying these ideas to the student’s lives. We look at elements of social critique in Korean pop songs, then find such critique in the performance script of the troupes.’ Mr Kim also commented that intangible cultural heritage is ‘an accumulation of experiences, lifestyles and cultures of people in certain areas. It is a great example of human adaptation to the environment, and their efforts to sustain communities and solve problems; thus, it is closely related to education. We expand the student’s temporal horizons by getting them to learn about past culture through the intangible heritage of the present day and predicting cultural changes in the future.’ In 2021, the project produced several guiding and outreach materials with lesson plans on how to integrate intangible heritage in schools, so that more schools across the region might enjoy such positive learning experience. These materials were transformed into a self-learning course for teachers and educators on GCED Online Campus, and a resource kit available in several languages. The project also produced a cohort of interdisciplinary educators in six pilot countries, namely Cambodia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyztan, Nepal, Republic of Korea and Thailand. ‘I have found that integrating living heritage into educational curricula is very useful for learners’, Mr Manit Ta-ai, Director of Ton Kaew Phadung Pitayalai School, in Chiang Mai, Thailand, commented on the subject of methodology. ‘The important thing is to provide our students with opportunities to think and analyze, so that it will reflect on their abilities to build their future upon various cultural assets they were born with, such as incorporating traditional knowledge to creative production of their own. Proving platforms and ways for students to learn directly from local masters can maximize the benefits of local cultural resources – both tangible and intangible heritage – to achieve inclusive and affordable education.’ This year, UNESCO is running quarterly challenges to teachers across Asia-Pacific, through UNESCO Associated Schools Network (ASPnet) and SEAMEO Schools’ Network. The three-step challenge calls for teachers to complete the GCED Online Campus course ‘Bringing Living Heritage to the Classroom in Asia-Pacific’, then to sign up for a regional webinar to wrap up their knowledge with the course developers, and finally to share with UNESCO their newly-developed lesson plans that integrate their local living heritage with the teaching of existing subjects. The first quarterly webinar, which took place on 30 September 2022, was attended by over 150 teachers across the region, with numerous lesson plans submitted by participants after its conclusion. The second quarterly webinar will take place on 1 December 2022, via Zoom conferencing. Teachers and educators interested in joining this growing community and taking up UNESCO’s challenge, thereby becoming eligible to earn up to three professional development certificates, can find further information at https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/teachers-living-heritage-online-course-engaging-class-culture The last step of the challenge – sharing your lesson plan with UNESCO – will end on 31 December 2022, after which UNESCO will respond directly to all submitters with comments for improving and actualizing their aspiring lesson plans.URL: https://bangkok.unesco.org/index.php/content/asia-pacific-teachers-embrace-unesco-challenge-bring-local-living-heritage-classrooms  The World Stands Together for Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2022 2022-10-30 ⓒ UNESCO The world is sending a clear message: Media and Information literacy is an imperative to nurture trust, freedom, peace and solidarity. Two days have passed since the beginning of the 11th Global Media and Information Literacy Week, which lasts until 31st October 2022. Its Feature Conference and Youth Forum is hosted by Nigeria and taking place in Abuja. However, the Week for Global Media and Information Literacy (MIL) is also being commemorated around the world. UNESCO has mobilized its MIL partners and networks to observe the Week with own celebrations and as of today, we are able to link up over 900 small and large events around the world, sending a thundering message of the urgency of media and information literacy at all levels of society. From Africa, the Arab States, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, numerous activities are being held to mark the occasion. Governments, private sector, digital platforms, civil society organizations, media actors and academics all have at heart to inform, train and reflect on the role of media and information literacy and its role in fostering trust, freedom, peace and solidarity. Africa In Rwanda, this edition of the Week is being used for masterclasses being held right now at the University of Kigali. Several small and medium-sized enterprises will learn how to take advantage of social media to ensure their business sustainability and growth. Arab States The Faculty of Mass Media at the Cairo University organizes a workshop to shed light on the role of Egyptian Women in promoting the Media and Information Literacy within the Egyptian community. Asia-Pacific In other parts of the world, young people from the digital literacy TikTok Korea have prepared online sessions, to combat the misuse of social media through training on strengthening the digital citizenship for adolescents. In Australia, some booksellers in the city of Blacktown organize a series of sessions to equip young people with techniques on how to evaluate the credibility of the information and the importance of obtaining information from several reliable sources. Europe The Secretary of State for Telecommunications and Digital Infrastructures in Spain has decided to mark the occasion with a day of debate on the impact that was recently approved by the General Law on Audiovisual Media and Media Literacy. In the Central Europe, at the Liceul Tehnologic Toma Socolescu in Ploiești, Romania, the students are exploring and learning about media and information literacy and its link with the right to education, and human rights. In Denmark, the MediaLitLab Foundation enters the scene with a hands-on workshop and role-playing on misinformation. The University of Copenhagen and the Copenhagen Business School organize a simulation exercise during which the students will experiment with the negative impacts of misinformation against the interests and values of society. Latin America In Santiago de Surco, Peru, where the celebrations take place in partnership with the University of Lima, a symposium on Media and Information Literacy, discusses the link between youth and media through the theme “Young people and the media, hurting trust?” Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2022: Do want to join the UNESCO’s celebrations? There is still time to participate! Watch virtual exhibition URL:https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/world-stands-together-global-media-and-information-literacy-week-2022

The World Stands Together for Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2022 2022-10-30 ⓒ UNESCO The world is sending a clear message: Media and Information literacy is an imperative to nurture trust, freedom, peace and solidarity. Two days have passed since the beginning of the 11th Global Media and Information Literacy Week, which lasts until 31st October 2022. Its Feature Conference and Youth Forum is hosted by Nigeria and taking place in Abuja. However, the Week for Global Media and Information Literacy (MIL) is also being commemorated around the world. UNESCO has mobilized its MIL partners and networks to observe the Week with own celebrations and as of today, we are able to link up over 900 small and large events around the world, sending a thundering message of the urgency of media and information literacy at all levels of society. From Africa, the Arab States, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, numerous activities are being held to mark the occasion. Governments, private sector, digital platforms, civil society organizations, media actors and academics all have at heart to inform, train and reflect on the role of media and information literacy and its role in fostering trust, freedom, peace and solidarity. Africa In Rwanda, this edition of the Week is being used for masterclasses being held right now at the University of Kigali. Several small and medium-sized enterprises will learn how to take advantage of social media to ensure their business sustainability and growth. Arab States The Faculty of Mass Media at the Cairo University organizes a workshop to shed light on the role of Egyptian Women in promoting the Media and Information Literacy within the Egyptian community. Asia-Pacific In other parts of the world, young people from the digital literacy TikTok Korea have prepared online sessions, to combat the misuse of social media through training on strengthening the digital citizenship for adolescents. In Australia, some booksellers in the city of Blacktown organize a series of sessions to equip young people with techniques on how to evaluate the credibility of the information and the importance of obtaining information from several reliable sources. Europe The Secretary of State for Telecommunications and Digital Infrastructures in Spain has decided to mark the occasion with a day of debate on the impact that was recently approved by the General Law on Audiovisual Media and Media Literacy. In the Central Europe, at the Liceul Tehnologic Toma Socolescu in Ploiești, Romania, the students are exploring and learning about media and information literacy and its link with the right to education, and human rights. In Denmark, the MediaLitLab Foundation enters the scene with a hands-on workshop and role-playing on misinformation. The University of Copenhagen and the Copenhagen Business School organize a simulation exercise during which the students will experiment with the negative impacts of misinformation against the interests and values of society. Latin America In Santiago de Surco, Peru, where the celebrations take place in partnership with the University of Lima, a symposium on Media and Information Literacy, discusses the link between youth and media through the theme “Young people and the media, hurting trust?” Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2022: Do want to join the UNESCO’s celebrations? There is still time to participate! Watch virtual exhibition URL:https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/world-stands-together-global-media-and-information-literacy-week-2022  Q&A: The Role of Teachers in Preventing and Addressing School Violence 2022-10-29 ⓒ myboys.me/Shutterstock.com What is school violence? School violence refers to all forms of violence, that takes place in and around schools and is experienced by students and perpetrated by other students, teachers and other school staff. This includes bullying and cyberbullying. Bullying is one of the most pervasive forms of school violence, affecting 1 in 3 young people. What forms may school violence take? Based on existing international surveys that collect data on violence in schools, UNESCO recognizes the following forms of school violence (recognising crossover between categories): Physical violence, which is any form of physical aggression with intention to hurt and includes: Physical violence perpetrated by peers, including physical fights (two students of about the same strength or power choosing to fight each other and physical attacks (one or more people hitting or striking a student with a weapon such as a stick, knife or gun). Physical violence perpetrated by teachers, which includes the intentional use of physical force with the potential to cause death, disability, injury or harm, regardless of whether it is used as a form or punishment (corporal punishment) or not. Psychological violence as verbal and emotional abuse, which includes any forms of isolating, rejecting, ignoring, insults, spreading rumors, making up lies, name-calling, ridicule, humiliation and threats, and psychological punishment. Sexual violence, which includes intimidation of a sexual nature, sexual harassment, unwanted touching, sexual coercion and rape, and it is perpetrated by a teacher, school staff or a schoolmate or classmate, and affects both girls and boys. Bullying as a pattern of behaviour rather than isolated incidents, which can be defined as intentional and aggressive behaviour occurring repeatedly against a victim where there is a real or perceived power imbalance and where the victims feel vulnerable and powerless to defend themselves. Bullying can take various forms: Physical bullying, including hitting, kicking and the destruction of property; Psychological bullying, such as teasing, insulting and threatening; or relational, through the spreading of rumours and exclusion from a group; and Sexual bullying, such as making fun of a victim with sexual jokes, comments or gestures, which may be defined as sexual ‘harassment’ in some countries. Cyberbullying is a form of psychological or sexual bullying that takes place online. Examples of cyberbullying include posting or sending electronic messages, including text, pictures or videos, aimed at harassing, threatening or targeting another person via a variety of media and social platforms such as online social networks, chat rooms, blogs, instant messaging and text messaging. Cyberbullying may also include spreading rumours, posting false information, hurtful messages, embarrassing comments or photos, or excluding someone from online networks or other communications. © UNESCO Who perpetrates school violence? School violence is perpetrated by students, teachers and other school staff. However, available evidence shows that violence perpetrated by peers is more common than by teachers and other school staff. What are the main reasons why children are bullied? All children can be bullied, yet evidence shows that children who are perceived to be “different” in any way are more at risk. Key factors include: Physical appearance; ethnic, linguistic or cultural differences including migrant and refugee status; gender, including not conforming to gender norms and stereotypes; social status including poverty; disability; and age. What are the consequences of school violence? Global comparable data are available only for the consequences of bullying, not for the consequences of other forms of school violence. Educational consequences – Being bullied undermines the sense of belonging at school and affects continued engagement in education. Children who are frequently bullied are more likely to feel like an outsider at school, and more likely to want to leave school after finishing secondary education. Children who are bullied have lower academic achievements than those who are not frequently bullied. Health consequences – Children’s mental health and well-being can be adversely impacted by bullying. Bullying is associated with higher rates of feeling lonely and suicidal, higher rates of smoking, alcohol and cannabis use and lower rates of self-reported life satisfaction and health. School violence can also cause physical injuries and harm. Why are teachers such an important part of the holistic approach to prevent and address school violence? Teachers are key to building a positive and supportive learning environment. They can: Provide quality education that develops students’ self-awareness, self-control, and interpersonal skills that are vital for healthy and respectful relationships; create psychologically and physically safe school and classroom environments; model caring and respectful relationships, and positive approaches to conflict management or discipline; guide students to take action themselves through student-led initiatives and peer approaches; recognize and respond to incidents of violence and connect students with referral services when needed; provide a link between school and community through their relationship with parents; and generate evidence and assessing what works at the school level. What support do teachers need to help create safe learning environments? A global online survey of teachers’ perceptions and practice in relation to school violence conducted by UNESCO in 2020 revealed that not all teachers are fully prepared to fulfill the role in preventing and addressing school violence: Almost half of the teachers surveyed say they received little or no training on school violence during their pre-service education, and more than two-thirds say that they have learned how to manage school violence through experience. Three in four teachers surveyed can identify physical and sexual violence yet are less likely to recognize some forms of psychological violence. Even if the teachers surveyed can identify school violence, and four in five say it is their responsibility to create a safe learning environment, they do not always intervene. Four in five help victims, but only half engage with students who witness violence. Teachers’ ability to positively influence school environments and to prevent or respond to violence, depends heavily on their preparation, in-service professional development, teaching standards, duties and workload. Other considerations include political leadership, legal and policy frameworks at national, local and school level, and support, resources and training. What are the linkages between school violence, school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) and violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression (SOGIE)? School violence may be perpetrated as a result of gender norms and stereotypes and enforced by unequal power dynamics – it is referred to as school-related gender-based violence. It includes, in particular, a specific type of gender-based violence, which is linked to the actual or perceived sexual orientation and gender identity or expression of victims, referred to as violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression, including homophobic and transphobic bullying. School-related gender-based violence is a significant part of school violence that requires specific efforts to address. Does school-related gender-based violence refer to sexual violence against girls only? No. School-related gender-based violence refers to all forms of school violence that is based on or driven by gender norms and stereotypes, which also includes violence against and between boys. Is school violence always gender-based? There are many factors that drive school violence. Gender is one of the significant drivers of violence but not all school violence is based on gender. Moreover, international surveys do not systematically collect data on the gendered nature of school violence, nor on violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression. Based on the analysis of global data, there are no major differences in the prevalence of bullying for boys and girls. However, there are some differences between boys and girls in terms of the types of bullying they experience. Boys are much more exposed to physical bullying, and to physical violence in general, than girls. Girls are slightly more exposed to psychological bullying, particularly through cyberbullying. According to the same data sexual bullying (sexual jokes, comments and gestures) affects the same proportion of boys and girls. Data coming from different countries, however, shows that girls are increasingly exposed to sexual bullying online. How does UNESCO help prevent and address school violence? The best available evidence shows that responses to school violence including bullying that are effective should be comprehensive or holistic, i.e. made of a combination of policies and interventions. Often this comprehensive response to school violence is referred to as a whole-school approach. Based on an extensive review of existing conceptual frameworks that describe that whole-school approach, UNESCO has identified the key components of a response that goes beyond schools and could be better described as a whole-education system or whole-education approach. These components are the following: Strong political leadership and robust legal and policy framework to address school violence; Training and support for teachers on school violence prevention and positive classroom management Curriculum, learning & teaching to promote, a caring (i.e. anti- school violence/anti-bullying) school climate and students’ social and emotional skills A safe psychological and physical school and classroom environment Reporting mechanisms for students affected by school violence, together with support and referral services Involvement of all stakeholders in the school community including parents Student empowerment and participation Collaboration and partnerships between the education sector and a wide range of partners (other government sectors, NGOs, academia) Evidence: monitoring of school violence including bullying and evaluation of responses - UNESCO’s work to prevent and address school violence and bullying URL:https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/qa-role-teachers-preventing-and-addressing-school-violence