News

Catch up on what’s happening in the world of global citizenship education.

1,657 results found

L’UNESCO donne l’alerte : si des mesures urgentes ne sont pas prises, 12 millions d’enfants n’iront jamais à l’école 2019-10-25 New data published today by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) on the world’s out-of-school children reveals little or no progress over more than a decade. Roughly 258 million children, adolescents and youth were out of school in 2018; around one sixth of the global population of school-age children (6 to 17 years old). Even more worrying is the fact that unless urgent measures are taken, 12 million primary school age children will never set foot in a school. In view of such figures, it will be difficult to ensure inclusive quality education for all, one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the international community for 2030. The new data on out-of-school children confirms recent UNESCO projections showing that, at the present rate, one in every six children will still be out of primary and secondary school in 2030, and that only six out of ten young people will complete secondary education. The data also highlights the gap between the world’s richest and poorest countries. According to UIS data, 19% of primary-age children (roughly 6 to 11 years old) are not in school in low-income countries, compared to just 2% in high-income countries. The gap grows wider still for older children and youth. About 61% of all youth between the ages of 15 and 17 are out of school in low-income countries, compared to 8% in high-income countries. “Girls continue to face the greatest barriers,” says Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO. “According to our projections, 9 million girls of primary school age will never start school or set foot in a classroom, compared to about 3 million boys. Four of those 9 million girls, live in sub-Saharan Africa, where the situation gives cause for even grater concern. We must therefore continue to centre our actions on girls’ and women’s education as an utmost priority.” “We have just 11 years to make good on the promise that every child will be in school and learning. Yet the new data shows us an unchanging and persistent picture of poor access and quality year after year,” says UIS Director Silvia Montoya. “These challenges are not inevitable. They can be overcome by a combination of intensive action and greater funding. We need real commitment from every single government, backed by resources, to get the job done.” While the number of out-of-school children appears to have dropped from 262 million in 2017, the fall is largely due to a methodological change in the way the indicators are calculated. As shown in a new paper, whereas primary school age children enrolled in pre-school, were previously included in the total, they are no longer counted as being out of school*. However, this does not change the overall rates of children out of school. The new data is released by the UIS – the custodian of SDG 4 data – a week before the United Nations General Assembly meets to examine progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals and to discuss the funding needed to achieve them. The data demonstrates the pressing need for more action to achieve quality education for all. This goal can still be reached, provided we renew our efforts while collecting more complete and reliable data to monitor progress on education access, completion and quality. * Until recently, all children of primary age (roughly 6 to 11 years) who were not enrolled in primary or secondary school were counted as being out of school. This included primary-age children who were still enrolled in pre-primary education. By removing this relatively small group of children (most of them in high-income countries), the total number of out-of-school children of primary age has been reduced by about 4.6 million. URL:https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-warns-without-urgent-action-12-million-children-will-never-spend-day-school-0

L’UNESCO donne l’alerte : si des mesures urgentes ne sont pas prises, 12 millions d’enfants n’iront jamais à l’école 2019-10-25 New data published today by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) on the world’s out-of-school children reveals little or no progress over more than a decade. Roughly 258 million children, adolescents and youth were out of school in 2018; around one sixth of the global population of school-age children (6 to 17 years old). Even more worrying is the fact that unless urgent measures are taken, 12 million primary school age children will never set foot in a school. In view of such figures, it will be difficult to ensure inclusive quality education for all, one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the international community for 2030. The new data on out-of-school children confirms recent UNESCO projections showing that, at the present rate, one in every six children will still be out of primary and secondary school in 2030, and that only six out of ten young people will complete secondary education. The data also highlights the gap between the world’s richest and poorest countries. According to UIS data, 19% of primary-age children (roughly 6 to 11 years old) are not in school in low-income countries, compared to just 2% in high-income countries. The gap grows wider still for older children and youth. About 61% of all youth between the ages of 15 and 17 are out of school in low-income countries, compared to 8% in high-income countries. “Girls continue to face the greatest barriers,” says Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO. “According to our projections, 9 million girls of primary school age will never start school or set foot in a classroom, compared to about 3 million boys. Four of those 9 million girls, live in sub-Saharan Africa, where the situation gives cause for even grater concern. We must therefore continue to centre our actions on girls’ and women’s education as an utmost priority.” “We have just 11 years to make good on the promise that every child will be in school and learning. Yet the new data shows us an unchanging and persistent picture of poor access and quality year after year,” says UIS Director Silvia Montoya. “These challenges are not inevitable. They can be overcome by a combination of intensive action and greater funding. We need real commitment from every single government, backed by resources, to get the job done.” While the number of out-of-school children appears to have dropped from 262 million in 2017, the fall is largely due to a methodological change in the way the indicators are calculated. As shown in a new paper, whereas primary school age children enrolled in pre-school, were previously included in the total, they are no longer counted as being out of school*. However, this does not change the overall rates of children out of school. The new data is released by the UIS – the custodian of SDG 4 data – a week before the United Nations General Assembly meets to examine progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals and to discuss the funding needed to achieve them. The data demonstrates the pressing need for more action to achieve quality education for all. This goal can still be reached, provided we renew our efforts while collecting more complete and reliable data to monitor progress on education access, completion and quality. * Until recently, all children of primary age (roughly 6 to 11 years) who were not enrolled in primary or secondary school were counted as being out of school. This included primary-age children who were still enrolled in pre-primary education. By removing this relatively small group of children (most of them in high-income countries), the total number of out-of-school children of primary age has been reduced by about 4.6 million. URL:https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-warns-without-urgent-action-12-million-children-will-never-spend-day-school-0  Too many teachers go it alone against the worldwide learning crisis 2019-10-23 Teaching is the most important job in the world; it impacts the growth and prosperity of both communities and nations. The prospects of any country's children cannot exceed the quality of its educators and yet, traditionally, limited focus has been placed on ensuring that all educators are equipped to succeed. It matters because it is universally agreed that we need to tackle the learning crisis for the one in two children being failed around the world who do not even pick up the basics of literacy and maths. The global Education Commission estimates that there as many as 600 million children in school struggling like this. This objective – Sustainable Development Goal 4 – underpins many of the other development goals. Teacher quality is the most important determinant of learning outcomes, but in many countries teachers are in short supply, isolated or not adequately supported. The good news is that this is increasingly becoming a focus for governments, investors, donors and multilaterals. Some leaders have already found innovative and low-cost ways to turn this around swiftly and at scale, but these flagship programmes are few and far between. Teachers under siege In many low- and middle-income countries, teaching is an extremely difficult profession. Once trained, teachers can find themselves working in a range of challenging situations: days away from the nearest town; little or no support or guidance; textbooks that aren’t aligned to the material or the age of the children they are attempting to teach; overcrowded classrooms with children sitting on the floor. Compounding all this is the sad truth that many teachers themselves often struggle with the content they are teaching; literacy and numeracy can be a challenge. In several sub-Saharan Africa countries, the average teacher does not perform much better on reading tests than the highest-performing Grade 6 or 12-year-old pupil. According to the World Bank report, teachers in low- and middle-income countries often lack the skills or motivation to teach effectively. The Education Commission notes that teachers currently only spend 45% of their time delivering instruction in the classroom. This lack of quality teaching results in poor outcomes, higher drop-out rate and long-term out-of-school children. Ultimately, the quality of education delivered is tied to how well a teacher is set up to succeed in his or her classroom. The status quo the world over is that teachers are often held accountable for outcomes without always being given the support and coaching they need to develop and grow their practice. Pockets of best practice Putting in place an ongoing support structure for teachers is vital. Helping them to create child-centred classrooms that focus on narrating the positive and fostering child-teacher relationships alongside access to grade-appropriate and carefully designed content are some of the ways that this can be done. One great example of where this is already happening is Edo state, Nigeria. There, across that whole state, thousands of government teachers have been upskilled and retooled. The impact on children’s learning has been significant. The initial analysis suggests that being in an EdoBEST school equates to nearly three-quarters of a year more maths instruction and nearly two-thirds of a year more literacy instruction compared to a normal Edo primary school. These are government teachers whose teaching effectiveness has been transformed through a tripartite programme of materials, support and development. This is a state in Nigeria where tens of thousands of children were out of school, where 60% of people live on or under the poverty line. It has been such a fast, large-scale impact it caught the eye of the World Bank and the Education World Forum as a case study for innovation. The governor who is leading this programme, Godwin Obaseki, had the vision and wisdom to understand that using a non-state actor, Bridge, as a technical partner was a powerful way to quickly up the quality of education for all children in free state schools. It is not only in Edo that this transformation is taking place. In Liberia, the same approach to teacher training and support in the public school system has seen an exponential increase in learning outcomes as part of a published RCT. Over the course of just one year, learning gains increased by 60%. Thanks to a comprehensive training package, support and resources were made available as part of the government’s transformative LEAP programme, which had teacher training and support at its core. New campaignThe new #TeachersTransformLives campaign builds on the transformation seen in these programmes, and advocates for better training and support for all teachers so that every teacher can succeed in the classroom. For example, this story of a teacher in Nigeria called Cecilia shows how one woman is having a big impact on her students. Fundamentally, we need to make sure that every teacher succeeds no matter how remote, isolated or impoverished their school and community. It’s possible for them to succeed with the right support and turn their classrooms into springboards for success in low-income communities anywhere in the world. URL:https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/10/too-many-teachers-go-it-alone-against-the-worldwide-learning-crisis/

Too many teachers go it alone against the worldwide learning crisis 2019-10-23 Teaching is the most important job in the world; it impacts the growth and prosperity of both communities and nations. The prospects of any country's children cannot exceed the quality of its educators and yet, traditionally, limited focus has been placed on ensuring that all educators are equipped to succeed. It matters because it is universally agreed that we need to tackle the learning crisis for the one in two children being failed around the world who do not even pick up the basics of literacy and maths. The global Education Commission estimates that there as many as 600 million children in school struggling like this. This objective – Sustainable Development Goal 4 – underpins many of the other development goals. Teacher quality is the most important determinant of learning outcomes, but in many countries teachers are in short supply, isolated or not adequately supported. The good news is that this is increasingly becoming a focus for governments, investors, donors and multilaterals. Some leaders have already found innovative and low-cost ways to turn this around swiftly and at scale, but these flagship programmes are few and far between. Teachers under siege In many low- and middle-income countries, teaching is an extremely difficult profession. Once trained, teachers can find themselves working in a range of challenging situations: days away from the nearest town; little or no support or guidance; textbooks that aren’t aligned to the material or the age of the children they are attempting to teach; overcrowded classrooms with children sitting on the floor. Compounding all this is the sad truth that many teachers themselves often struggle with the content they are teaching; literacy and numeracy can be a challenge. In several sub-Saharan Africa countries, the average teacher does not perform much better on reading tests than the highest-performing Grade 6 or 12-year-old pupil. According to the World Bank report, teachers in low- and middle-income countries often lack the skills or motivation to teach effectively. The Education Commission notes that teachers currently only spend 45% of their time delivering instruction in the classroom. This lack of quality teaching results in poor outcomes, higher drop-out rate and long-term out-of-school children. Ultimately, the quality of education delivered is tied to how well a teacher is set up to succeed in his or her classroom. The status quo the world over is that teachers are often held accountable for outcomes without always being given the support and coaching they need to develop and grow their practice. Pockets of best practice Putting in place an ongoing support structure for teachers is vital. Helping them to create child-centred classrooms that focus on narrating the positive and fostering child-teacher relationships alongside access to grade-appropriate and carefully designed content are some of the ways that this can be done. One great example of where this is already happening is Edo state, Nigeria. There, across that whole state, thousands of government teachers have been upskilled and retooled. The impact on children’s learning has been significant. The initial analysis suggests that being in an EdoBEST school equates to nearly three-quarters of a year more maths instruction and nearly two-thirds of a year more literacy instruction compared to a normal Edo primary school. These are government teachers whose teaching effectiveness has been transformed through a tripartite programme of materials, support and development. This is a state in Nigeria where tens of thousands of children were out of school, where 60% of people live on or under the poverty line. It has been such a fast, large-scale impact it caught the eye of the World Bank and the Education World Forum as a case study for innovation. The governor who is leading this programme, Godwin Obaseki, had the vision and wisdom to understand that using a non-state actor, Bridge, as a technical partner was a powerful way to quickly up the quality of education for all children in free state schools. It is not only in Edo that this transformation is taking place. In Liberia, the same approach to teacher training and support in the public school system has seen an exponential increase in learning outcomes as part of a published RCT. Over the course of just one year, learning gains increased by 60%. Thanks to a comprehensive training package, support and resources were made available as part of the government’s transformative LEAP programme, which had teacher training and support at its core. New campaignThe new #TeachersTransformLives campaign builds on the transformation seen in these programmes, and advocates for better training and support for all teachers so that every teacher can succeed in the classroom. For example, this story of a teacher in Nigeria called Cecilia shows how one woman is having a big impact on her students. Fundamentally, we need to make sure that every teacher succeeds no matter how remote, isolated or impoverished their school and community. It’s possible for them to succeed with the right support and turn their classrooms into springboards for success in low-income communities anywhere in the world. URL:https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/10/too-many-teachers-go-it-alone-against-the-worldwide-learning-crisis/  Youth Activists for Climate Change 2019-10-23 ContextGlobal emissions are reaching record levels and show no sign of peaking. The impacts of climate change are being felt everywhere and are having very real consequences on people’s lives. Climate change is dis-rupting national economies, costing us dearly today and even more tomorrow. But there is a growing recognition that affordable, scalable solutions are available now that will enable us all to leapfrog to cleaner, more resilient economies. The United Nations System recognizes the key role that youth play in tackling climate change and works closely with youth-led and youth-focussed organizations around the world. ActionIn 2017, UNESCO Office, Jakarta and UN CC:Learn (One UN Climate Change Learning Partnership) orga-nized the “Youth Leadership Camp for Climate Change”. The programme was to provide them with an un-derstanding of climate change in agriculture and energy, marine and fisheries and forestry sectors. At the end of the camp, three youths were selected to participate in the Tribal Climate Camp in Washington DC, USA to build their capacity to address climate change and associated economic, social, cultural, regulato-ry, and technological trends and impacts within and between communities. In 2019, UN held the first-ever, UN Youth Climate Summit. The UN Youth Climate Summit was a platform for young climate action leaders to showcase their solutions at the United Nations and to meaningfully engage with decision-makers on the defining issue of our time. The Summit was attended by over 600 outstanding youth climate champions chosen from around the world, including young representatives from seven biosphere reserves from Southeast Asia and Pacific. They are Ms Ari Iswandari (Leuser National Park, Indonesia), Mr Hamid Arrum Harahap (Batang Toru, Indo-nesia), Ms Sukma Riverningtyas (Lore Lindu National Park, Indonesia), Mr Rey Antony Ostria (Albay Bio-sphere Reserve, the Philippines), Ms Kanoktip Somsiri (Sakaerat Biosphere Reserve, Thailand), Ms Cao Ngu-yen (Cu Lao Cham Biosphere Reserve, Vietnam) and Mr Onneil Nena (Utwe Biosphere Reserve, Federated States of Micronesia). These outstanding young leaders were nominated to participate based on their demonstrated commitment to addressing the climate crisis and advancing solutions. During the Summit, the youths shared specific conditions and examples from their region and Biosphere Reserve sites. ImpactThe Youth Climate Summit featured a full-day of programmes that brought together young activists, inno-vators, entrepreneurs, and change makers committed to combating climate change at the pace and scale needed to meet the climate challenge. The programme culminated in unveiling the ActNow platform that encourages people to take action on climate action. The youths will continue taking positive climate ac-tion. URL:https://en.unesco.org/news/youth-activists-climate-change

Youth Activists for Climate Change 2019-10-23 ContextGlobal emissions are reaching record levels and show no sign of peaking. The impacts of climate change are being felt everywhere and are having very real consequences on people’s lives. Climate change is dis-rupting national economies, costing us dearly today and even more tomorrow. But there is a growing recognition that affordable, scalable solutions are available now that will enable us all to leapfrog to cleaner, more resilient economies. The United Nations System recognizes the key role that youth play in tackling climate change and works closely with youth-led and youth-focussed organizations around the world. ActionIn 2017, UNESCO Office, Jakarta and UN CC:Learn (One UN Climate Change Learning Partnership) orga-nized the “Youth Leadership Camp for Climate Change”. The programme was to provide them with an un-derstanding of climate change in agriculture and energy, marine and fisheries and forestry sectors. At the end of the camp, three youths were selected to participate in the Tribal Climate Camp in Washington DC, USA to build their capacity to address climate change and associated economic, social, cultural, regulato-ry, and technological trends and impacts within and between communities. In 2019, UN held the first-ever, UN Youth Climate Summit. The UN Youth Climate Summit was a platform for young climate action leaders to showcase their solutions at the United Nations and to meaningfully engage with decision-makers on the defining issue of our time. The Summit was attended by over 600 outstanding youth climate champions chosen from around the world, including young representatives from seven biosphere reserves from Southeast Asia and Pacific. They are Ms Ari Iswandari (Leuser National Park, Indonesia), Mr Hamid Arrum Harahap (Batang Toru, Indo-nesia), Ms Sukma Riverningtyas (Lore Lindu National Park, Indonesia), Mr Rey Antony Ostria (Albay Bio-sphere Reserve, the Philippines), Ms Kanoktip Somsiri (Sakaerat Biosphere Reserve, Thailand), Ms Cao Ngu-yen (Cu Lao Cham Biosphere Reserve, Vietnam) and Mr Onneil Nena (Utwe Biosphere Reserve, Federated States of Micronesia). These outstanding young leaders were nominated to participate based on their demonstrated commitment to addressing the climate crisis and advancing solutions. During the Summit, the youths shared specific conditions and examples from their region and Biosphere Reserve sites. ImpactThe Youth Climate Summit featured a full-day of programmes that brought together young activists, inno-vators, entrepreneurs, and change makers committed to combating climate change at the pace and scale needed to meet the climate challenge. The programme culminated in unveiling the ActNow platform that encourages people to take action on climate action. The youths will continue taking positive climate ac-tion. URL:https://en.unesco.org/news/youth-activists-climate-change  Statistical Group to Consider 53 Changes to SDG Indicators 2019-10-23 Story Highlights The IAEG-SDGs will address 53 proposals for revision, replacement, addition and deletion within the global SDG indicator framework. New indicators are proposed on breastfeeding, mental health, AMR, energy use by tourism, migrant deaths, pledges to the GCF, and GHG emissions and concentrations, among other issues. 10 October 2019: The UN Inter-Agency and Expert Group on the SDG Indicators is considering 53 suggested changes to the SDG indicator framework based on input gathered through an open consultation. The IAEG-SDGs is expected to agree on a final set of proposals during its upcoming tenth meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. As part of the 2020 Comprehensive Review of the indicator framework called for in a 2017 UN General Assembly resolution, the IAEG held an “open call” in late May and June 2019 for proposed changes to the SDG indicators. It received approximately 200 proposals for additions, deletions, replacements and revisions to the indicators, including 25 suggestions of additional indicators. IAEG members then reduced this input to 53 proposals for a consultation held in August and early September 2019. Among those currently proposed for addition are indicators on: SDG 2: anemia, low birthweight and breastfeeding; SDG 3: mental disorders, public spending on primary health care, and antimicrobial resistance (AMR); SDG 4: tertiary education enrollment ratio by sex; SDG 8: energy use by tourism industries; SDG 10: Palma ratio, Gini coefficient and migrant deaths at borders; SDG 13: GHG emissions, GHG concentrations, number of NAPs, and pledges to the Green Climate Fund (GCF); SDG 15: Living Planet Index; SDG 16: refugees as a proportion of origin country’s population; and SDG 17: TOSSD – Total Official Support for Sustainable Development. The comments received on these and other proposals can be seen in the Excel file titled, ‘Compilations of inputs received during the Open Consultation,’ at this page. IAEG members are reviewing the most recent input and in some cases requesting further information. The Group aims to finalize a revised set of proposals on 21 October 2019 during a one-day meeting open only to IAEG members. Other countries and stakeholders can discuss the resulting proposals during the plenary segment of the meeting taking place from 22-24 October. Following IAEG-SDG 10, the Group will make any needed refinements before submitting its proposal to the UN Statistical Commission ahead of its 51st session in March 2020. The IAEG has set out guiding principles for the 2020 Comprehensive Review process. These include not imposing significant additional burdens on national statistical work, and limiting the scope of changes to keep the overall size of the indicator framework approximately the same. Therefore, it is expected that replacement indicators are more likely to be agreed upon than additional indicators. The tenth IAEG-SDGs meeting (agenda here) also will: consider seven tier reclassification requests based on data availability; discuss work plans for the Tier III indicators not proposed for reclassification nor included in the 2020 review; and discuss data disaggregation, indicators and targets with a 2020 deadline, and “other SDG data initiatives” for monitoring the Goals. The most recent reclassification of an indicator was to SDG indicator 12.6.1 on the number of companies publishing sustainability reports, which was moved from Tier III to Tier II in September 2019. More information on the tier classification of the indicators is available here. [UN Statistics Division webpage on 2020 comprehensive review] [IAEG-SDGs homepage] [SDG Knowledge Hub sources] related events:10th Meeting of the UN Inter-Agency and Expert Group on the SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs) URL:https://sdg.iisd.org/news/statistical-group-to-consider-53-changes-to-sdg-indicators/

Statistical Group to Consider 53 Changes to SDG Indicators 2019-10-23 Story Highlights The IAEG-SDGs will address 53 proposals for revision, replacement, addition and deletion within the global SDG indicator framework. New indicators are proposed on breastfeeding, mental health, AMR, energy use by tourism, migrant deaths, pledges to the GCF, and GHG emissions and concentrations, among other issues. 10 October 2019: The UN Inter-Agency and Expert Group on the SDG Indicators is considering 53 suggested changes to the SDG indicator framework based on input gathered through an open consultation. The IAEG-SDGs is expected to agree on a final set of proposals during its upcoming tenth meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. As part of the 2020 Comprehensive Review of the indicator framework called for in a 2017 UN General Assembly resolution, the IAEG held an “open call” in late May and June 2019 for proposed changes to the SDG indicators. It received approximately 200 proposals for additions, deletions, replacements and revisions to the indicators, including 25 suggestions of additional indicators. IAEG members then reduced this input to 53 proposals for a consultation held in August and early September 2019. Among those currently proposed for addition are indicators on: SDG 2: anemia, low birthweight and breastfeeding; SDG 3: mental disorders, public spending on primary health care, and antimicrobial resistance (AMR); SDG 4: tertiary education enrollment ratio by sex; SDG 8: energy use by tourism industries; SDG 10: Palma ratio, Gini coefficient and migrant deaths at borders; SDG 13: GHG emissions, GHG concentrations, number of NAPs, and pledges to the Green Climate Fund (GCF); SDG 15: Living Planet Index; SDG 16: refugees as a proportion of origin country’s population; and SDG 17: TOSSD – Total Official Support for Sustainable Development. The comments received on these and other proposals can be seen in the Excel file titled, ‘Compilations of inputs received during the Open Consultation,’ at this page. IAEG members are reviewing the most recent input and in some cases requesting further information. The Group aims to finalize a revised set of proposals on 21 October 2019 during a one-day meeting open only to IAEG members. Other countries and stakeholders can discuss the resulting proposals during the plenary segment of the meeting taking place from 22-24 October. Following IAEG-SDG 10, the Group will make any needed refinements before submitting its proposal to the UN Statistical Commission ahead of its 51st session in March 2020. The IAEG has set out guiding principles for the 2020 Comprehensive Review process. These include not imposing significant additional burdens on national statistical work, and limiting the scope of changes to keep the overall size of the indicator framework approximately the same. Therefore, it is expected that replacement indicators are more likely to be agreed upon than additional indicators. The tenth IAEG-SDGs meeting (agenda here) also will: consider seven tier reclassification requests based on data availability; discuss work plans for the Tier III indicators not proposed for reclassification nor included in the 2020 review; and discuss data disaggregation, indicators and targets with a 2020 deadline, and “other SDG data initiatives” for monitoring the Goals. The most recent reclassification of an indicator was to SDG indicator 12.6.1 on the number of companies publishing sustainability reports, which was moved from Tier III to Tier II in September 2019. More information on the tier classification of the indicators is available here. [UN Statistics Division webpage on 2020 comprehensive review] [IAEG-SDGs homepage] [SDG Knowledge Hub sources] related events:10th Meeting of the UN Inter-Agency and Expert Group on the SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs) URL:https://sdg.iisd.org/news/statistical-group-to-consider-53-changes-to-sdg-indicators/  Youth-driven initiatives promotes safe learning environment for girls in Tanzanian schools 2019-10-23 At Ngweli Secondary School in Sengerema district of Tanzania, safe space-TUSEME (“Let’s speak out” in Swahili) youth club members are running a school cafeteria. ‘It was for us to have safe food’, shared student leader Said Ramadhan Rashid. When the school did not have a cafeteria, students used to go out to find food vendors in the neighbourhood. Food from street vendors was often not clean enough. ‘Now, we are serving safe food for our peers. To set up this cafeteria, club members raised funds through a fundraising event. Bringing together peers, teachers, and community members, they collected enough fund to build a space and hire a community member to cook and serve the food in addition to the seed money provided by UNESCO. Milk tea, doughnuts, and some snacks are among the items being served now. As the rainy season is coming in Tanzania, students plan to set up a plastic roof to protect the cafeteria from rain. They are also looking into expanding their business into vegetable gardening. Youth club members also run weekly peer-to-peer campaigns encouraging studying and promoting a safe learning environment. Changes have taken place in school life. ‘We are happier to come to school. Violence has decreased between students, from teachers and parents because we have been empowered to speak out. And we are motived to study hard’, said a form three student (third year at lower secondary school), Ested Omary Ramandhani. ‘Club activities provide an important opportunity for students to achieve specific goals through their own initiatives’, said Amani Mbeyale, a Geography teacher mentoring the TUSEME club members. ‘From initiating an entrepreneurship project to running peer-to-peer support campaigns, girls and boys learn how to collaborate, communicate and solve problems while gaining confidence and improving their academic performance.’ Safe Space-TUSEME youth club encourages student-led activities to enhance adolescent girls' self-confidence and determination in remaining in school. The club is based on the combined concepts of Safe Space developed by UNESCO and TUSEME (Let’s Speak Out in Swahili) by Forum for African Women Educationalist. Students identify challenges in their school and discuss ways to address them. Similar initiatives were seen in other participating schools where peer support groups were created. For example, the youth club in Nyampulukano Secondary School discusses corporal punishment with teacher and parents. The Kilabela Secondary School club is piloting a school dormitory to address the long commute to school, often affecting girls’ attendance and increasing truancy in schools. Since May 2019, about 200 clubs were established in four districts of Tanzania – Sengerema, Mkoani, Ngorongoro, and Kasulu engaging more than 4,200 students as part of the UN Joint Programme project in Tanzania, Empowering Adolescent Girls and Young Women through Education. In partnership with UNFPA and UN Women, the project is supported by the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). More information: UNESCO-UNFPA-UN Women Joint Programme UNESCO’s work on education and gender equality URL:http://www.unescodar.or.tz/unescodar/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=568:youth-driven-initiatives-promotes-safe-learning-environment-for-girls-in-tanzanian-schools&catid=107:rokstories-samples&Itemid=510

Youth-driven initiatives promotes safe learning environment for girls in Tanzanian schools 2019-10-23 At Ngweli Secondary School in Sengerema district of Tanzania, safe space-TUSEME (“Let’s speak out” in Swahili) youth club members are running a school cafeteria. ‘It was for us to have safe food’, shared student leader Said Ramadhan Rashid. When the school did not have a cafeteria, students used to go out to find food vendors in the neighbourhood. Food from street vendors was often not clean enough. ‘Now, we are serving safe food for our peers. To set up this cafeteria, club members raised funds through a fundraising event. Bringing together peers, teachers, and community members, they collected enough fund to build a space and hire a community member to cook and serve the food in addition to the seed money provided by UNESCO. Milk tea, doughnuts, and some snacks are among the items being served now. As the rainy season is coming in Tanzania, students plan to set up a plastic roof to protect the cafeteria from rain. They are also looking into expanding their business into vegetable gardening. Youth club members also run weekly peer-to-peer campaigns encouraging studying and promoting a safe learning environment. Changes have taken place in school life. ‘We are happier to come to school. Violence has decreased between students, from teachers and parents because we have been empowered to speak out. And we are motived to study hard’, said a form three student (third year at lower secondary school), Ested Omary Ramandhani. ‘Club activities provide an important opportunity for students to achieve specific goals through their own initiatives’, said Amani Mbeyale, a Geography teacher mentoring the TUSEME club members. ‘From initiating an entrepreneurship project to running peer-to-peer support campaigns, girls and boys learn how to collaborate, communicate and solve problems while gaining confidence and improving their academic performance.’ Safe Space-TUSEME youth club encourages student-led activities to enhance adolescent girls' self-confidence and determination in remaining in school. The club is based on the combined concepts of Safe Space developed by UNESCO and TUSEME (Let’s Speak Out in Swahili) by Forum for African Women Educationalist. Students identify challenges in their school and discuss ways to address them. Similar initiatives were seen in other participating schools where peer support groups were created. For example, the youth club in Nyampulukano Secondary School discusses corporal punishment with teacher and parents. The Kilabela Secondary School club is piloting a school dormitory to address the long commute to school, often affecting girls’ attendance and increasing truancy in schools. Since May 2019, about 200 clubs were established in four districts of Tanzania – Sengerema, Mkoani, Ngorongoro, and Kasulu engaging more than 4,200 students as part of the UN Joint Programme project in Tanzania, Empowering Adolescent Girls and Young Women through Education. In partnership with UNFPA and UN Women, the project is supported by the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). More information: UNESCO-UNFPA-UN Women Joint Programme UNESCO’s work on education and gender equality URL:http://www.unescodar.or.tz/unescodar/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=568:youth-driven-initiatives-promotes-safe-learning-environment-for-girls-in-tanzanian-schools&catid=107:rokstories-samples&Itemid=510  Two years after exodus, Myanmar’s ‘desperate’ Rohingya youth need education, skills: UNICEF 2019-10-22 The daily struggle to survive for Myanmar’s Rohingya people in one of the world’s largest refugee settlements, has caused “overwhelming” despair and jeopardized the hopes of an entire generation, the head of the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Henrietta Fore, said on Friday. In a report marking two years since the arrival of around 745,000 Rohingya civilians in Bangladesh - after fleeing State-led persecution and violence in Myanmar - Executive Director Fore appealed for urgent investment in education and skills training. ‘Mere survival is not enough’ “For the Rohingya children and youth now in Bangladesh, mere survival is not enough,” she said. “It is absolutely critical that they are provided with the quality learning and skills development that they need to guarantee their long-term future.” Without adequate learning opportunities, youngsters can fall prey to drug dealers and traffickers who offer to smuggle “desperate” ethnic Rohingya out of Bangladesh, the UN report warned. Education ‘can help avoid risks’ Women and girls face harassment and abuse especially at night, UNICEF noted, while adding that one of the agency’s objectives through education is to give teenagers the skills they need to deal avoid “many risks”, including early marriage for girls. In addition to Bangladesh’s Kutupalong camp, which is home to some 630,000 people, hundreds of thousands more, have found shelter in another dozen or so camps in the Cox’s Bazar region close to the Myanmar border. Living conditions are often described as perilous by UN humanitarians, including UNICEF, which have issued frequent alerts about the devastating effects of monsoon rains on flimsy bamboo and tarpaulin shelters. Between 21 April and 18 July this year, refugee camp authorities recorded 42 injuries and 10 fatalities, including six children, because of monsoon weather, according to UNICEF. Amid huge needs - and with conditions still unsuitable for the return of ethnic Rohingya to Myanmar, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) - basic public services have been provided in Cox’s Bazar, including health care, nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene, under the leadership of Bangladesh. “But as the refugee crisis drags on, children and young people are clamouring for more than survival; they want quality education that can provide a path to a more hopeful future,” the UNICEF report insists. According to the agency, around 280,000 children aged four to 14, now receive educational support. Of this number, 192,000 of them are in 2,167 learning centres, but more than 25,000 children “are not attending any learning programmes”, the agency noted. Most 15 to 18-year-olds miss out on school More worrying still, nearly all 15 to 18-year-olds are “not attending any type of educational facility”, UNICEF said, before highlighting the case of one Kutupalong resident, Abdullah, 18. “I studied six subjects back in Myanmar,” Abdullah says. “But when I arrived here, there was no way I could continue. If we do not get education in the camps, I think our situation is going to be dire.” In an appeal to the Governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar, UNICEF and other agencies are calling for the use of national educational resources – curricula, training manuals and assessment methods – to help provide more structured learning for Rohingya children. “Providing learning and training materials is a huge task and can only be realized with the full backing of a range of partners,” UNICEF chief Ms. Fore said. “But the hopes of a generation of children and adolescents are at stake. We cannot afford to fail them.” URL:https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044321

Two years after exodus, Myanmar’s ‘desperate’ Rohingya youth need education, skills: UNICEF 2019-10-22 The daily struggle to survive for Myanmar’s Rohingya people in one of the world’s largest refugee settlements, has caused “overwhelming” despair and jeopardized the hopes of an entire generation, the head of the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Henrietta Fore, said on Friday. In a report marking two years since the arrival of around 745,000 Rohingya civilians in Bangladesh - after fleeing State-led persecution and violence in Myanmar - Executive Director Fore appealed for urgent investment in education and skills training. ‘Mere survival is not enough’ “For the Rohingya children and youth now in Bangladesh, mere survival is not enough,” she said. “It is absolutely critical that they are provided with the quality learning and skills development that they need to guarantee their long-term future.” Without adequate learning opportunities, youngsters can fall prey to drug dealers and traffickers who offer to smuggle “desperate” ethnic Rohingya out of Bangladesh, the UN report warned. Education ‘can help avoid risks’ Women and girls face harassment and abuse especially at night, UNICEF noted, while adding that one of the agency’s objectives through education is to give teenagers the skills they need to deal avoid “many risks”, including early marriage for girls. In addition to Bangladesh’s Kutupalong camp, which is home to some 630,000 people, hundreds of thousands more, have found shelter in another dozen or so camps in the Cox’s Bazar region close to the Myanmar border. Living conditions are often described as perilous by UN humanitarians, including UNICEF, which have issued frequent alerts about the devastating effects of monsoon rains on flimsy bamboo and tarpaulin shelters. Between 21 April and 18 July this year, refugee camp authorities recorded 42 injuries and 10 fatalities, including six children, because of monsoon weather, according to UNICEF. Amid huge needs - and with conditions still unsuitable for the return of ethnic Rohingya to Myanmar, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) - basic public services have been provided in Cox’s Bazar, including health care, nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene, under the leadership of Bangladesh. “But as the refugee crisis drags on, children and young people are clamouring for more than survival; they want quality education that can provide a path to a more hopeful future,” the UNICEF report insists. According to the agency, around 280,000 children aged four to 14, now receive educational support. Of this number, 192,000 of them are in 2,167 learning centres, but more than 25,000 children “are not attending any learning programmes”, the agency noted. Most 15 to 18-year-olds miss out on school More worrying still, nearly all 15 to 18-year-olds are “not attending any type of educational facility”, UNICEF said, before highlighting the case of one Kutupalong resident, Abdullah, 18. “I studied six subjects back in Myanmar,” Abdullah says. “But when I arrived here, there was no way I could continue. If we do not get education in the camps, I think our situation is going to be dire.” In an appeal to the Governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar, UNICEF and other agencies are calling for the use of national educational resources – curricula, training manuals and assessment methods – to help provide more structured learning for Rohingya children. “Providing learning and training materials is a huge task and can only be realized with the full backing of a range of partners,” UNICEF chief Ms. Fore said. “But the hopes of a generation of children and adolescents are at stake. We cannot afford to fail them.” URL:https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044321  ‘We are facing a learning crisis’, UN chief warns on International Youth Day 2019-10-22 Transforming Education is the theme for this year, which comes at a time when the world is facing a “learning crisis”, says Mr Guterres, and students need not only to learn, “but to learn how to learn”. The UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), which is co-organising the Day alongside the UN Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO), says that statistics demonstrate that significant transformations are still required to make education systems more inclusive and accessible: only 10% of people have completed upper secondary education in low income countries; 40 % of the global population is not taught in a language they speak or fully understand; and over 75 % of secondary school age refugees are out of school. Ensuring access to inclusive and equitable education, and promoting lifelong learning, is one of the goals of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and International Youth Day 2019, will present examples that show how education is changing to meet modern challenges. The role of young people as champions of inclusive and accessible education is also being highlighted, as youth-led organizations are helping to transform education, through lobbying, advocacy, and partnerships with educational institutions. “Education today should combine knowledge, life skills and critical thinking”, said Mr. Guterres. It should include information on sustainability and climate change. And it should advance gender equality, human rights and a culture of peace”. All these elements are included in Youth 2030, the UN’s strategy to scale up global, regional and national actions to meet young people’s needs, realize their rights and tap their possibilities as agents of change. URL:https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044091

‘We are facing a learning crisis’, UN chief warns on International Youth Day 2019-10-22 Transforming Education is the theme for this year, which comes at a time when the world is facing a “learning crisis”, says Mr Guterres, and students need not only to learn, “but to learn how to learn”. The UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), which is co-organising the Day alongside the UN Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO), says that statistics demonstrate that significant transformations are still required to make education systems more inclusive and accessible: only 10% of people have completed upper secondary education in low income countries; 40 % of the global population is not taught in a language they speak or fully understand; and over 75 % of secondary school age refugees are out of school. Ensuring access to inclusive and equitable education, and promoting lifelong learning, is one of the goals of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and International Youth Day 2019, will present examples that show how education is changing to meet modern challenges. The role of young people as champions of inclusive and accessible education is also being highlighted, as youth-led organizations are helping to transform education, through lobbying, advocacy, and partnerships with educational institutions. “Education today should combine knowledge, life skills and critical thinking”, said Mr. Guterres. It should include information on sustainability and climate change. And it should advance gender equality, human rights and a culture of peace”. All these elements are included in Youth 2030, the UN’s strategy to scale up global, regional and national actions to meet young people’s needs, realize their rights and tap their possibilities as agents of change. URL:https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044091  Abuse of junior students an incubator of hatred 2019-10-22 This picture posted on the Anti-Sotus Facebook page shows an initiation activity held early this month at the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok. The photos are shocking. The first shows young men in their underwear lying on the beach; in the second, one man is apparently licking ketchup from another’s chest. A third shows men lining up in two rows seemingly simulating sex. The images were posted on the Anti-Sotus Facebook page, which stands against the creed of Seniority, Order, Tradition, Unity and Spirit that is supposedly meant to encourage student bonding in universities. According to the page, the leaked photos came from an initiation activity held earlier this month for first-year students from the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok. The issue has gone viral on social media, been reported on by news agencies and sparked public outrage. The Anti-Sotus page itself issued a statement with a set of demands, including an investigation into the matter. The department was quick to respond with its own statement, saying it was not aware of the “privately held” activity and an investigation was under way. This is not the first time such initiation activities, called rub nong in Thai, roughly translating to “welcome the youngsters”, have caused widespread public anger. The problem has long been present in Thai society, with social media allowing anecdotes and photographic evidence to be easily shared and amplifying the public’s awareness. The online world also serves as a forum for public discussion and outrage. Just a few internet searches generate a long list of initiation rituals involving unhygienic activities, humiliation, harassment and physical abuse in many forms of dehumanising bullying. Some include students being forced to pass sweets mouth-to-mouth, kiss the ground and eat a mixture of food intended to look like faeces. Other reports detail verbal abuse, physical violence and sexual harassment. Male students are at risk of more violent activities and, alarmingly, some of the rituals can also be found in high schools. Younger students have no choice. Failure or refusal to participate can lead to negative consequences such as being ignored or ostracised by peers and upper-level students. While education institutions generally have policies against violent and degrading rituals, such practices continue in disguise or in secret. When a whistle-blower leaks evidence of abuse to the public, a witch-hunt often ensues. Ironically, but unsurprisingly, the cycle is perpetuated as some first-year students are willing or pressured to continue the legacy of power relations established by terror when they become sophomores. Initiation activities supposedly help students bond with each other, but that unity is achieved at a price. Initiations involving violence and bullying in higher education are not unique to Thailand and affect victims in many ways, including lifelong psychological trauma or, in extreme cases, fatalities. In one high-profile case in 2014, a 16-year-student died during a hazing incident at a beach in Prachuap Kiri Khan; another 19-year-old ended up in critical care after nearly drowning in Chon Buri in 2016.UNESCO’s 2017 Global Status Report on School Violence and Bullying is extremely relevant to this social ill, detailing the impacts of violence and bullying. For educational outcomes, the consequences include missing classes, poor academic performance and dropping out. Regarding mental and emotional health, victims are more likely to experience interpersonal difficulties, be depressed, have low self-esteem and attempt suicide. Unsafe learning environments create a climate of fear and insecurity with the perception that the well-being of students is not important. The quality of education is drastically compromised. What are the solutions? The report suggests several responses to handle this kind of problem. Develop and enforce laws and policies that protect learners from violence and bullying. Create safe and inclusive learning environments. Train teaching staff members to use curricula approaches that prevent violence and to respond appropriately to incidents. Raise awareness of the negative impact of violence and bullying. Provide confidential reporting mechanisms and counselling. Implement data collection and monitoring. The list goes on. In Thailand, however, these degrading rub nong rituals have been caught in a vicious cycle. When there is news of this kind of abuse, people fly into a rage. Education institutions respond by implementing regulatory measures. However, when the fire dies down, everyone forgets. Regulations are relaxed, and as nasty or even nastier behaviour reappears. The cycle has been running in circles for decades. How can we put an end to it? The latest scandal is once again an opportunity for society to join hands and pledge that this abusive initiation culture must end. Education institutes and faculty members are obliged to set a precedent showing that violent rituals cannot be accepted, not just blithely dismiss such incidents as benighted students fooling around. These students will eventually graduate from the education system and contribute to society — are these the values and behaviours that we want to be empowered in our society? Parents and the public also must not tolerate abusive activities and can take action by pressuring schools and universities to take action and create safe learning spaces for all. Social media can be a platform to advocate for a culture of more supportive initiations and to campaign against violence and bullying. Students play an important role. First-year students should assertively stand up for themselves to protect their welfare and dignity, but they must have better support. Importantly, upper-level students have to take responsibility for their actions. There is no reason that rub nong rituals have to focus on degradation and sadism. This problem is not new. Constructive solutions are not unimaginable. Let’s put in more effort to ensure that education institutes truly serve as incubators of integrity and peace. URL:https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/abuse-junior-students-incubator-hatred

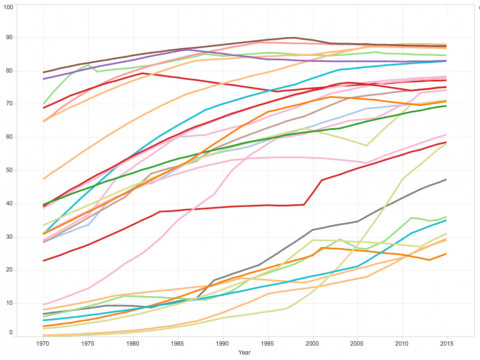

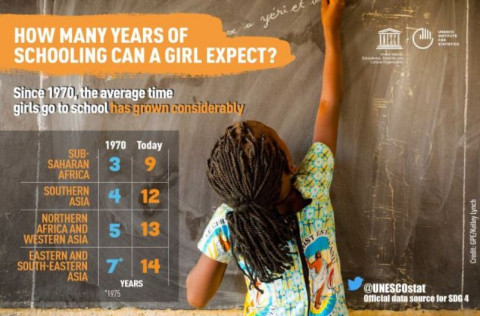

Abuse of junior students an incubator of hatred 2019-10-22 This picture posted on the Anti-Sotus Facebook page shows an initiation activity held early this month at the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok. The photos are shocking. The first shows young men in their underwear lying on the beach; in the second, one man is apparently licking ketchup from another’s chest. A third shows men lining up in two rows seemingly simulating sex. The images were posted on the Anti-Sotus Facebook page, which stands against the creed of Seniority, Order, Tradition, Unity and Spirit that is supposedly meant to encourage student bonding in universities. According to the page, the leaked photos came from an initiation activity held earlier this month for first-year students from the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok. The issue has gone viral on social media, been reported on by news agencies and sparked public outrage. The Anti-Sotus page itself issued a statement with a set of demands, including an investigation into the matter. The department was quick to respond with its own statement, saying it was not aware of the “privately held” activity and an investigation was under way. This is not the first time such initiation activities, called rub nong in Thai, roughly translating to “welcome the youngsters”, have caused widespread public anger. The problem has long been present in Thai society, with social media allowing anecdotes and photographic evidence to be easily shared and amplifying the public’s awareness. The online world also serves as a forum for public discussion and outrage. Just a few internet searches generate a long list of initiation rituals involving unhygienic activities, humiliation, harassment and physical abuse in many forms of dehumanising bullying. Some include students being forced to pass sweets mouth-to-mouth, kiss the ground and eat a mixture of food intended to look like faeces. Other reports detail verbal abuse, physical violence and sexual harassment. Male students are at risk of more violent activities and, alarmingly, some of the rituals can also be found in high schools. Younger students have no choice. Failure or refusal to participate can lead to negative consequences such as being ignored or ostracised by peers and upper-level students. While education institutions generally have policies against violent and degrading rituals, such practices continue in disguise or in secret. When a whistle-blower leaks evidence of abuse to the public, a witch-hunt often ensues. Ironically, but unsurprisingly, the cycle is perpetuated as some first-year students are willing or pressured to continue the legacy of power relations established by terror when they become sophomores. Initiation activities supposedly help students bond with each other, but that unity is achieved at a price. Initiations involving violence and bullying in higher education are not unique to Thailand and affect victims in many ways, including lifelong psychological trauma or, in extreme cases, fatalities. In one high-profile case in 2014, a 16-year-student died during a hazing incident at a beach in Prachuap Kiri Khan; another 19-year-old ended up in critical care after nearly drowning in Chon Buri in 2016.UNESCO’s 2017 Global Status Report on School Violence and Bullying is extremely relevant to this social ill, detailing the impacts of violence and bullying. For educational outcomes, the consequences include missing classes, poor academic performance and dropping out. Regarding mental and emotional health, victims are more likely to experience interpersonal difficulties, be depressed, have low self-esteem and attempt suicide. Unsafe learning environments create a climate of fear and insecurity with the perception that the well-being of students is not important. The quality of education is drastically compromised. What are the solutions? The report suggests several responses to handle this kind of problem. Develop and enforce laws and policies that protect learners from violence and bullying. Create safe and inclusive learning environments. Train teaching staff members to use curricula approaches that prevent violence and to respond appropriately to incidents. Raise awareness of the negative impact of violence and bullying. Provide confidential reporting mechanisms and counselling. Implement data collection and monitoring. The list goes on. In Thailand, however, these degrading rub nong rituals have been caught in a vicious cycle. When there is news of this kind of abuse, people fly into a rage. Education institutions respond by implementing regulatory measures. However, when the fire dies down, everyone forgets. Regulations are relaxed, and as nasty or even nastier behaviour reappears. The cycle has been running in circles for decades. How can we put an end to it? The latest scandal is once again an opportunity for society to join hands and pledge that this abusive initiation culture must end. Education institutes and faculty members are obliged to set a precedent showing that violent rituals cannot be accepted, not just blithely dismiss such incidents as benighted students fooling around. These students will eventually graduate from the education system and contribute to society — are these the values and behaviours that we want to be empowered in our society? Parents and the public also must not tolerate abusive activities and can take action by pressuring schools and universities to take action and create safe learning spaces for all. Social media can be a platform to advocate for a culture of more supportive initiations and to campaign against violence and bullying. Students play an important role. First-year students should assertively stand up for themselves to protect their welfare and dignity, but they must have better support. Importantly, upper-level students have to take responsibility for their actions. There is no reason that rub nong rituals have to focus on degradation and sadism. This problem is not new. Constructive solutions are not unimaginable. Let’s put in more effort to ensure that education institutes truly serve as incubators of integrity and peace. URL:https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/abuse-junior-students-incubator-hatred  Données à fournir pour les femmes 2019-10-22 Gender equality is a key priority for tracking progress towards the achievement of all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 4 on quality education for all. If an education indicator can be broken down by sex, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) disaggregates it – from pre-school enrolment to PhD students, and from the percentage of women teachers to whether women researchers are equally represented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses. If there are different trends for girls and boys at different ages as they make their way through the education system, we want to know why. We carefully sift through the world’s data to see if girls are being taught in schools that are safe and supportive, with all the facilities they need. And if girls are out of school, we want to know where they are, how many of them there are, and why they are not in the classroom. The UIS has updated its eAtlas of Gender Inequality in Education to coincide with the Women Deliver conference. The interactive maps provide a one-stop, at-a-glance resource packed with data on all of these issues. 1. Individual power Education is critical for individual power. Until we have gender equality in education, it is hard – if not impossible – to picture a world where power is shared equally between women and men, and where the SDGs have been achieved. Consider the benefits, which span every SDG, from poverty reduction to the creation of peaceful societies. Just one additional year of schooling can increase a woman's earnings by up to 20%. Education is also a safeguard against child, early and forced marriage, with the risks of early childbirth, violence and limited prospects: each year of secondary education reduces the likelihood of marrying as a child by five percentage points or more. And it helps to reduce child mortality: a child whose mother can read is 50% more likely to live past the age of five. Overall, the world is moving in the right direction: the gender gap in education is closing and has been closing for decades. The majority of girls worldwide now complete primary school and we are close to gender parity at the primary level of education. Girls are also in school for longer than ever before. As 50 years of data produced by the UIS show, girls’ school life expectancy – the number of years they spend in school – is on the rise. 50 years ago a girl starting school in the world’s Least Developed Countries would receive less than three years of education. Today, she can expect almost nine years. 2. Structural power We must address some major structural problems on the quality of education, as well as access. Worldwide, we have an estimated 617 million children and adolescents who are not reaching even the minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. And we have 262 million children – one in every five – who are out of school.Girls are less likely than boys to make the transition to secondary school in the poorest regions of the world, with barriers to their education that begin at the primary level becoming ever more difficult to overcome. If you are a girl from a poor family, living in a remote village or an urban slum, with a disability, or from a marginalised community, the barriers can become unbearable. As a result, just 2% of the poorest girls in low-income countries currently complete upper secondary school, and there are gender disparities in secondary education across the global south, according to the World Inequality on Education Database (WIDE), a joint product of the UIS and the Global Education Monitoring Report. Worldwide, there are more young women than men enrolled in higher education – particularly in the wealthiest nations. But their numbers fall at the very highest levels of education, with far fewer women gaining a PhD and women accounting for less than 30% of researchers globally. Part of the solutions lie in giving schools, teachers and entire education systems the power to deliver an education of high quality to each and every child. That demands equity in access to schooling and equity within the classroom, with girls given the same opportunities as boys to participate and to excel in all subjects. Education equity needs to be measured, of course – an area where the UIS has been working closely with national statistical agencies for many years. One of the structural challenges that needs our diligent attention is to build the capacity of statistical gathering mechanisms and models – whether they are within the ministry of education or national statistical agencies – to ensure that developing countries are better able to gather, analyse, and report on girls’ progress in education and learning. This is particularly important in conflict and crisis affected situations where war, instability, fragility and protracted conflict can limit a government’s ability to accurately gather and analyse evidence. Given that in conflict and crisis situations, girls are less likely to access or to complete their education, it remains of particular concern that we find ways to accurately gather disaggregated data and report on results. 3. The power of movements SDG 4 emerged from a global recognition that education and learning are crucial for progress on everything else. The UIS continues to work with countries, technical partners and donors to produce the data needed to strengthen the education sector and ensure that every child is going to school and learning. A leading partner of the UIS, the Government of Canada is one of the world’s champions for sex disaggregated data and gender statistics . In addition to supporting and hosting the UIS since it’s inception, the Government of Canada championed the endorsement in 2018 of the G7 Charlevoix Declaration on Quality Education for Girls, Adolescent Girls and Women in Developing Countries, which recognises that data and evidence help to empower women and girls to fulfil their potential and, therefore, helps the world deliver on its commitments to the SDGs. So we’re delighted that delegates from around the world are in Vancouver and hope that the Women Deliver conference will draw attention to the need for more and better disaggregated data and evidence to drive progress on education and, by extension, progress for women and girls. URL:http://uis.unesco.org/en/blog/data-deliver-women

Données à fournir pour les femmes 2019-10-22 Gender equality is a key priority for tracking progress towards the achievement of all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 4 on quality education for all. If an education indicator can be broken down by sex, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) disaggregates it – from pre-school enrolment to PhD students, and from the percentage of women teachers to whether women researchers are equally represented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses. If there are different trends for girls and boys at different ages as they make their way through the education system, we want to know why. We carefully sift through the world’s data to see if girls are being taught in schools that are safe and supportive, with all the facilities they need. And if girls are out of school, we want to know where they are, how many of them there are, and why they are not in the classroom. The UIS has updated its eAtlas of Gender Inequality in Education to coincide with the Women Deliver conference. The interactive maps provide a one-stop, at-a-glance resource packed with data on all of these issues. 1. Individual power Education is critical for individual power. Until we have gender equality in education, it is hard – if not impossible – to picture a world where power is shared equally between women and men, and where the SDGs have been achieved. Consider the benefits, which span every SDG, from poverty reduction to the creation of peaceful societies. Just one additional year of schooling can increase a woman's earnings by up to 20%. Education is also a safeguard against child, early and forced marriage, with the risks of early childbirth, violence and limited prospects: each year of secondary education reduces the likelihood of marrying as a child by five percentage points or more. And it helps to reduce child mortality: a child whose mother can read is 50% more likely to live past the age of five. Overall, the world is moving in the right direction: the gender gap in education is closing and has been closing for decades. The majority of girls worldwide now complete primary school and we are close to gender parity at the primary level of education. Girls are also in school for longer than ever before. As 50 years of data produced by the UIS show, girls’ school life expectancy – the number of years they spend in school – is on the rise. 50 years ago a girl starting school in the world’s Least Developed Countries would receive less than three years of education. Today, she can expect almost nine years. 2. Structural power We must address some major structural problems on the quality of education, as well as access. Worldwide, we have an estimated 617 million children and adolescents who are not reaching even the minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. And we have 262 million children – one in every five – who are out of school.Girls are less likely than boys to make the transition to secondary school in the poorest regions of the world, with barriers to their education that begin at the primary level becoming ever more difficult to overcome. If you are a girl from a poor family, living in a remote village or an urban slum, with a disability, or from a marginalised community, the barriers can become unbearable. As a result, just 2% of the poorest girls in low-income countries currently complete upper secondary school, and there are gender disparities in secondary education across the global south, according to the World Inequality on Education Database (WIDE), a joint product of the UIS and the Global Education Monitoring Report. Worldwide, there are more young women than men enrolled in higher education – particularly in the wealthiest nations. But their numbers fall at the very highest levels of education, with far fewer women gaining a PhD and women accounting for less than 30% of researchers globally. Part of the solutions lie in giving schools, teachers and entire education systems the power to deliver an education of high quality to each and every child. That demands equity in access to schooling and equity within the classroom, with girls given the same opportunities as boys to participate and to excel in all subjects. Education equity needs to be measured, of course – an area where the UIS has been working closely with national statistical agencies for many years. One of the structural challenges that needs our diligent attention is to build the capacity of statistical gathering mechanisms and models – whether they are within the ministry of education or national statistical agencies – to ensure that developing countries are better able to gather, analyse, and report on girls’ progress in education and learning. This is particularly important in conflict and crisis affected situations where war, instability, fragility and protracted conflict can limit a government’s ability to accurately gather and analyse evidence. Given that in conflict and crisis situations, girls are less likely to access or to complete their education, it remains of particular concern that we find ways to accurately gather disaggregated data and report on results. 3. The power of movements SDG 4 emerged from a global recognition that education and learning are crucial for progress on everything else. The UIS continues to work with countries, technical partners and donors to produce the data needed to strengthen the education sector and ensure that every child is going to school and learning. A leading partner of the UIS, the Government of Canada is one of the world’s champions for sex disaggregated data and gender statistics . In addition to supporting and hosting the UIS since it’s inception, the Government of Canada championed the endorsement in 2018 of the G7 Charlevoix Declaration on Quality Education for Girls, Adolescent Girls and Women in Developing Countries, which recognises that data and evidence help to empower women and girls to fulfil their potential and, therefore, helps the world deliver on its commitments to the SDGs. So we’re delighted that delegates from around the world are in Vancouver and hope that the Women Deliver conference will draw attention to the need for more and better disaggregated data and evidence to drive progress on education and, by extension, progress for women and girls. URL:http://uis.unesco.org/en/blog/data-deliver-women  Respecter l'engagement de l'ODD4.a: Donner plus de pouvoir aux apprenants handicapés 2019-10-22 Persons with disabilities are said to be the world’s largest minority, with generally poor health conditions, low education achievements, few economic opportunities and high rates of poverty. This is largely due to the lack of services available to them. With the pledge to leave no one behind in the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, this year’s theme on International Day of Persons with Disabilities on 3 December focuses on empowering persons with disabilities as both beneficiaries and change agents for inclusive, equitable and sustainable development. The term ‘disability’ refers to physical, sensory, cognitive and/or intellectual impairment, and also to mental illnesses and various types of chronic disease. The current reality is that children with disabilities tend not to attend school. As the UNESCO Institute for Statistics showed back in March 2018, in Cambodia 57% of children with disabilities were out school. Conversely, the population aged 15-29 with disabilities who had attended school at all showed the lowest attendance rates of 44% in Viet Nam 2009 and 53% in Indonesia. We know that learners with disabilities require specialized education. But are we considering whether school facilities are adequate enough to accommodate these learners? The Education 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goal 4 have formulated Target 4.a on building and upgrading education facilities that are, among other criteria, disability-sensitive to provide inclusive and effective learning environments – for all. To track this target with regards to disability, the proportion of schools with adapted infrastructure and materials for students with disabilities must be monitored. However, currently available data allows for little interpretation as Member States have yet to collect and submit relevant metrics on adapted infrastructure, in this case for disability. Despite the limited data for the few countries shown in the below figure, they are indicative of the missing infrastructure that would allow children, adolescents and youth with disabilities to attend school. When everyday necessities, even simply going to the washroom, are an impossibility because doorways are impassible, or the road to school cannot be navigated, in addition to the lack of disability-friendly learning materials, let alone assistive technologies, is it surprising that even those who have attended school at some point often do not continue to attend? Target 4.a addresses creating and maintaining welcoming and safe learning spaces for learners with disabilities. It does not pretend to be the entire solution for ensuring disability-inclusive education; we know that children with special needs require specialized education, which in turn requires specialized teacher training, as well as holistically designed policies and plans that ensure a legal and regulatory environment to access education. What is more, we should not forget that ensuring learners are able to access such spaces is another precondition for them to participate. That could mean encouraging parents to have their children attend school, abolishing discriminatory practices in teaching and admissions, and ensuring public transport infrastructure is available to help access schools in the first place. URL:https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/honouring-sdg4a-pledge-empowering-learners-disabilities